You’ll learn all the necessary network nomenclature (such as the

difference between client/server and peer-to-peer),

hardware requirements, the ins and outs of cabling, protocol

descriptions, and lots more. You can think of this section as your

initiation into the black art of networking, except, as you’ll see,

things aren’t as black as they used to be.

If you just have a single

computer in your office or at home, and if you’re the only person who

uses that computer, your setup is inherently efficient. You can use the

machine whenever you like, and everything you need—your applications,

your printer, your CD-ROM drive, your modem, and so on—will be readily

available.

Things become

noticeably less efficient if you have to share the computer with other

people. Then you might have to wait for someone else to finish a task

before you can get your own work done; you might need to have separate

applications for each person’s requirements; and you might need to set

up separate folders to hold each person’s data. Windows XP’s user

accounts and Fast User Switching features ease these problems, but they

don’t eliminate them. However, although this solution might ease some of

the burden, it won’t eliminate it entirely. For example, you might

still have to twiddle a thumb or two while waiting for another person to

complete his work.

A better solution is to

increase the number of computers available. Now that machines with fast

processors, ample RAM, and massive hard disk space can be had for less

than $1,000, a multiple-machine setup is an affordable proposition for

small offices. Even at home, the current trend is to buy a nice system

for mom and dad to put in their office, while the kids inherit the old

machine for their games and homework assignments.

Multiple machines, however, bring with them new inefficiencies:

In many

cases, it’s just not economically feasible to supply each computer with

its own complete set of peripherals. Printers, for example, are a

crucial part of the computing equation—when you need them. If someone

needs a printer only a couple of times a week, it’s hard to justify

shelling out hundreds of dollars so that person can have his or her own

printer. The problem, then, is how to share a printer (or whatever)

among several machines.

These

days, few people work in splendid isolation. Rather, the norm is that

colleagues and coworkers often have to share data and work together on

the same files. If everyone uses a separate computer, how are they

supposed to share files?

Most

offices have standardized on particular software packages for word

processing, spreadsheets, graphics, and other mainstream applications.

Does this mean that you have to purchase a copy of an expensive software

program or suite for each machine? As with peripherals, what do you do

about a person who uses a program only sporadically?

Everyone

wants on the Internet, of course, but paying a subscription for each

user seems wasteful. What’s needed is a way to share a single Internet

connection.

Yes,

you can overcome these limitations. To share a printer, for example,

you could simply lug it from machine to machine, as needed, or else get a

100-foot parallel cable that can be plugged into whichever computer

needs access to the printer. This won’t work if you need to share an

internal CD-ROM drive, however. For data, there’s always the old

“sneaker net” solution: Plop the files on a floppy disk and run them

back and forth between computers. As for applications, you could install

some programs on a single machine and require users to share, but that

brings us back to the original problem of multiple people sharing a

single machine.

There has to be a better way.

For example, wouldn’t it be better if you could simply attach a

peripheral to a single machine and make it possible for any other

computer to access that peripheral whenever it is needed? Wouldn’t it be

better if users could easily move documents back and forth between

computers, or had a common storage area for shared files? Wouldn’t it be

better if you installed an application in only one location and

everyone could run the program on his own machine at will?

Well, I’m happy to report that there is a better way, and it’s called networking.

The underlying idea of a network is simple: You connect multiple

machines by running special cables from one computer to another. These

cables plug into adapter cards (called network interface cards;

I’ll talk more about them later in this chapter) that are installed

inside each computer. With this basic card/cable combination—or even a

wireless setup—and a network-aware operating system (such as Windows

XP), you can solve all the inefficiencies just described:

A printer (or just about any peripheral) that’s attached to one machine can be used by any other machine on the network.

Files can be transferred along the cables from one computer to another.

Users

can access disk drives and folders on network computers as though they

were part of their own computer. In particular, you can set up a folder

to store common data files, and each user will be able to access these

files from the comfort of her machine. (For security, you can restrict

access to certain folders and drives.)

You

can install an application on one machine and set things up so that

other machines can run the application without having to install the

entire program on their local hard drive. There’s no such thing as a

free lunch, however. You have to purchase a license to install the

application on the other computers. However, depending on how many users

you have, buying a license is usually cheaper than buying additional

full-blown copies of the application.

You can set up an Internet connection on one machine and share that connection with other machines on the network.

Not only are the problems

solved, but a whole new world of connected computing becomes available.

For example, you can establish an email system so that users can send

messages to each other via the network. You can use groupware applications that enable users to collaborate on projects, schedules, and documents. As the administrator of the network, you can remotely manage other computers, such as installing new software or customizing the environment for each user.

It sounds great, but are

there downsides to all of this? Yes. Unfortunately, there is no such

thing as a networking nirvana just yet. In all, you have three main

concerns:

| Security | This

is a big issue, to be sure, because you’re giving users access to

resources outside their own computers. You must set things up so that

people can’t damage files or invade other peoples’ privacy,

intentionally or otherwise. |

| Speed | Network

connections are fast, but they’re not as fast as a local hard drive.

So, running networked applications or working with remote documents

won’t have quite the snap that users might prefer. |

| Setup | Networked

computers are inherently harder to set up and maintain than standalone

machines. Difficulties include the initial tribulations of installing

and configuring networking cards and running cables, as well as the

ongoing issues of sharing resources, setting up passwords, and so on. |

The benefits of

connectivity, however, greatly outweigh the disadvantages, so budding

network administrators shouldn’t be dissuaded by these few quibbles. Now

that I’ve convinced you that a network is a good thing, let’s turn our

attention to the types of networks you can set up.

LANs, WANs, MANs, and More

Networks come in three basic flavors: local area networks, internetworks, and wide area networks:

| Local area network (LAN) | A

LAN is a network in which all the computers occupy a relatively small

geographical area, such as a department, office, home, or building. In a

LAN, all the connections between computers are made via network cables. |

| Internetwork | An internetwork is a network that combines two or more LANs by means of a special device, such as a bridge or a router. Internetworks are often called internets for short, but they shouldn’t be confused with the Internet, the global collection of networks. |

| Wide area network (WAN) | A

WAN is a network that consists of two or more LANs or internet works

spaced out over a relatively large geographical area, such as a state, a

country, or the world. The networks in a WAN typically are connected

via high-speed, fiber-optic phone lines, microwave dishes, or satellite

links. |

|

The current popularity of the Internet is spilling over into corporate networks. Management information systems (MIS)

types all over the world have seen how Internet technology can be both

cost-effective and scalable, so they’ve been wondering how to deliver

the same benefits on the corporate level. The result is an intranet:

The implementation of Internet technologies such as TCP/IP and World

Wide Web servers for use within a corporate organization rather than for

connection to the Internet as a whole.

A related network species is the extranet.

In this case, Internet technologies are used to give external

users—such as customers and employees in other offices—access to a

corporate TCP/IP network. For example, many online banks use an extranet

to provide web browser–based banking over a secure private connection.

|

Note

Network resources are usually divided into two categories: local and remote. Not to be confused with the local in local area network, a local resource

is any peripheral, file, folder, or application that is either attached

directly to your computer or resides on your computer’s hard disk. By

contrast, a remote resource is any peripheral, file, folder, or

application that exists somewhere on the network.

Other types of networks also exist. A campus network

connects all the buildings in a school campus or an industrial park.

Such networks often span large geographical areas, like WANs, but use

private cabling to connect their subnetworks. A metropolitan area network (MAN) connects computers in a city or county and is usually regulated by a municipal or state utility commission. Finally, an enterprise network

connects all the computers within an organization, no matter how

geographically diverse the computers might be, and no matter what kinds

of operating systems and network protocols are used in individual

segments of the network.

Client/Server Versus Peer-to-Peer

It used to be that the

dominant network model revolved around a single, monolithic computer

with massive amounts of storage space and processing power. Attached to

this behemoth were many dumb terminals—essentially

just a keyboard and monitor—that contained no local storage and no

processing power. Instead, the central mainframe or minicomputer was

used for all data storage and to run all applications.

The advent of the PC,

however, has more or less sounded the death knell for the dumb terminal.

Not surprisingly, users prefer having local disks so that they can keep

their data close at hand and run their own applications. (This is,

after all, the personal

computer we’re talking about.) To accommodate the PC revolution, two

new kinds of network models have become dominant: client/server and

peer-to-peer.

Client/Server Networks

In general, the client/server model

splits the computing workload into two separate, yet related, areas. On

one hand, you have users working at intelligent front-end systems called clients. In turn, these client machines interact with powerful back-end systems called servers.

The basic idea is that the clients have enough processing power to

perform tasks on their own, but they rely on the servers to provide them

with specialized resources or services, or access to information that

would be impractical to implement on a client (such as a large

database).

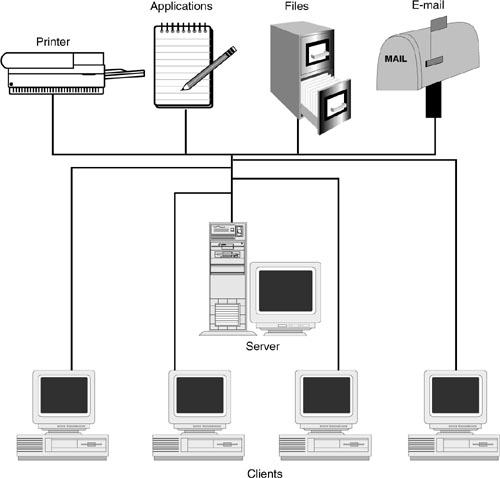

This client/server

relationship forms the basis of many network operating systems. In this

case, a server computer provides various network-related services, such

as access to resources (a network printer, for example), centralized

file storage, password verification and other security measures,

server-based application setup, email, data backups, and access to

external networks (such as the Internet).

The various client PCs,

although they have their own storage and processing power, interact

with the server whenever they need access to network-related resources

or services, as illustrated in Figure 1. Client computers are also referred to as nodes or workstations.

Note that in most

client/server networks, the server computer can perform only server

duties. In other words, you can’t use it as a client to run

applications.

In this client/server networking model, two types of software are required:

| Network operating systemNOS) ( | This

software runs on the server and provides the various network services

for the clients. The range of services available depends on the NOS.

NetWare, for example, provides not only file and print services, but

also email, communications, and security services. Other network

operating systems that use the client/server model are Windows 2003

Server and UNIX. |

| Client software | This

software provides applications that run on the client machine with a

way to request services and resources from the server. If an application

needs a local resource, the client software forwards the request to the

local operating system; if an application needs a server resource, the

client software redirects the request to the network operating system.

Windows XP provides clients for Microsoft networks and NetWare networks. |

For small LANs, a

single server is usually sufficient for handling all client requests. As

the LAN grows, however, the load on the server increases and network

performance can suffer. Nothing in the client/server model restricts a

network to a single server, however. So, to ease the server burden, most

large LANs utilize multiple servers. In distributed networks,

administrators are free to organize the servers’ duties in any way that

maximizes network performance. For example, administrators can split

clients into workgroups and assign each group to a specific server.

Similarly, they can split the duties performed by each server. For

example, one server could handle file services, whereas another could

handle print services, and so on.

Peer-to-Peer Networks

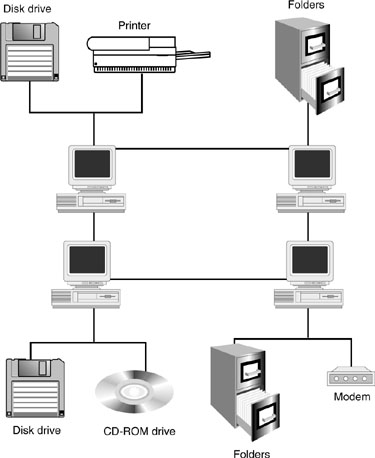

In a peer-to-peer network,

no computer is singled out to provide special services. Instead, all

the computers attached to the network have equal status (at least as far

as the network is concerned), and all the computers can act as both

servers and clients, as illustrated in Figure 2.

On the server side, each computer can share any of its resources with the network and

control access to these shared resources. For example, if a user shares

a folder with the network, she also can set up passwords to restrict

access to that folder.

On the client side, each

computer can work with the resources that have been shared by the other

peers on the network (assuming that it has permission to do so, of

course).

Which One Should You Choose?

If you’re thinking

about networking a few computers, should you go with a client/server

setup or a peer-to-peer model? That’s a tough question to answer because

it depends on so many factors: the number of computers you want to

connect, the operating system (or systems) you’re using, the services you need, the amount of money you have available to spend, and so on.

In general, the smaller

the network, the more sense the peer-to-peer model makes. This is

particularly true if you’re running Windows XP because it’s designed as a

peer-to-peer NOS. After you’ve installed your network cards and run

your cables, you’re more or less ready to go. Windows XP’s automatic

hardware detection usually does a pretty good job of recognizing and

configuring the network hardware, and the network client makes it easy

to share and access network resources.

If, rather than

just a few computers, you have a few dozen, you’ll have to go the

client/server route. Large peer-to-peer setups are just too unwieldy to

maintain and administer, and performance quickly drops off as you add

more nodes. A top-of-the-line client/server NOS (such as Windows 2003

Server or NetWare) comes with remote administration, scales nicely as

you add more clients and servers, and is robust enough to handle large

loads. The price you pay for all this power is, well, the price: These

big-time operating systems are expensive and usually require an extra

hardware investment beyond the standard

card/cable combo. And with power comes complexity. Unlike the relative

simplicity of their peer-to-peer counterparts, administration of

medium-to-large client/server networks isn’t for the faint of heart.