11.1. Putting a Price Tag on Your Project

It's

the old chicken-and-egg scenario—which comes first, the project budget

or the project cost estimates? Either way, the organization wants to

know how much the project will cost. Or, looking at it from the other

direction—what's the maximum this project should cost to get the financial benefit the organization requires?

The

financial benefit comes down to whether the project is worth the

effort. How much money will the project make or how much will it save?

What will it cost to get that result? For example, suppose the R&D

eggheads have a fabulous idea for a new thingamabob that will

revolutionize helium balloon distribution. The bean counters think sales

could peak at $200,000 in the first year and then would drop off

incrementally, earning $400,000 over the product's life cycle. The

company has to decide how much they're willing to spend on the

development project and how much profit they need to earn to make the

project worthwhile. As the project manager, you're expected to provide

cost estimates based on the agreed-upon project scope. The hard part is

making the two figures agree with each other.

If

you're in the enviable position of proposing the budget, one approach

is to develop your schedule, assign resources to tasks, and let Project

calculate the resulting costs. You can use that cost figure as you go,

hat in hand, to present the budget. The powers that be often reduce that

number, although they also set aside contingency funds and management

reserve as insurance.

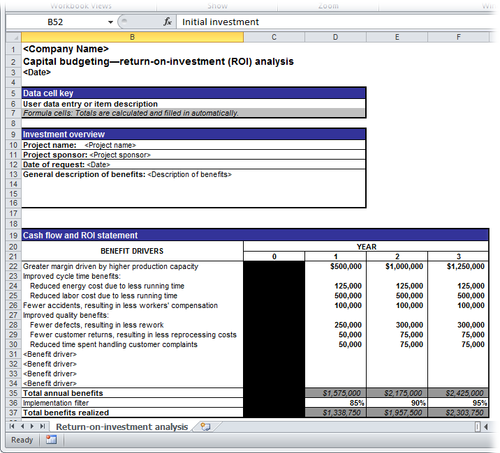

A more scientific method for setting the project budget is capital budgeting,

which is a set of financial calculations that help determine a

project's potential rate of return, return on investment, and payback

period.

Capital budgeting can also show the impact of not taking on other

projects while the organization's resources are busy with the current

project. Thus, capital budgeting analysis can help an organization

determine whether a project is in line with its financial and other

strategic goals—with the result of a go/no-go decision for that project.

For an example, you can download an Excel capital budgeting template from Microsoft Office Online (http://tinyurl.com/ROIWorksheet).

Enter your data, and the spreadsheet calculates the rate of return on

an investment, the net present value of the investment, and the payback

period, as shown in Figure 1.

If

you create a work breakdown structure, assign resources, and specify

costs for those resources, Project can give you a total cost estimate

for the project. The program also breaks it down into its component

parts—total costs for a resource, total costs for a phase, even costs

for an individual task.

When

you compare the amount determined in the capital budgeting analysis

with your project's cost estimates, you can see how far apart they are.

This comparison is valuable for deciding whether the project is even

feasible. For example, suppose the capital budget analysis shows that

the project is worth doing as long as the cost doesn't exceed $50,000.

If your project cost estimate perches steadfastly at $200,000, chances

are good that the project won't fly, because trimming 75 percent from

the estimate isn't likely.

Keep in mind that project

budgeting is an iterative process. The project sponsor may have a

ballpark number in mind, but you can help hone that number with your

project cost

estimate and give the budget a basis in reality. Explanations and

negotiations may ensue, along with further analysis, until finally you

obtain a realistic project budget figure that everyone is willing to

accept.

Remember that you

need to do everything in your power to not exceed that budget once the

project gets under way. If you overshoot the budget, you may have to pay

dearly, in unpopular schedule adjustments, reduced scope, cost

overruns, not to mention your own reputation. In the end, people say two

things about successful projects: "It came in on time and under

budget."

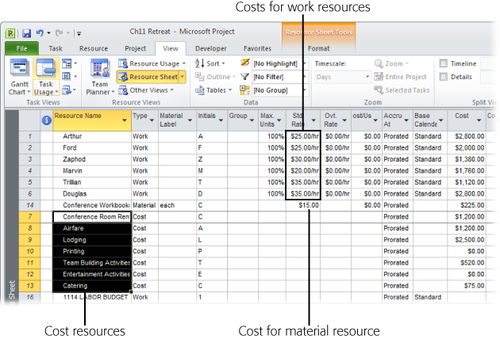

2. Incorporating Resource Costs

Resource

costs are often the lion's share of project cost. They include the

human resources and equipment that perform project tasks (work resources), as well as the consumable materials and supplies used while carrying out a task (material resources). To make sure you have accurate costs in your project plan, check that you've entered all resource costs. You enter costs for work and material resources in the Resource Sheet (see Figure 2).

Introduced in Project 2007, cost resources

represent things that are instrumental to completing a task but don't

include work time, duration, or an amount of material consumed. Examples

of cost resources are travel costs, room rentals, printing services,

training costs, and so on. These costs affect the project price tag, but

not the project schedule.

Like work and material resources, you create a cost resource in the Resource Sheet .

Unlike work and material resources, however, you don't enter the cost

in the Resource Sheet. Instead, you enter the cost after you assign the

cost resource to a task .