According to Microsoft, an object

is a distinct and named entity in the network infrastructure that has

its own set of attributes and elements. There are many different types

of objects:

Users

Computers

Printers

Contacts

Groups

Shared folders

Domain controllers

Organizational units

inetOrgPersons

MSMQ queue aliases

Within Active Directory, each

of these objects can be assigned various permissions through the use of

access control lists. Permissions are binary in nature; that is,

something is either allowed or not allowed.

And beyond each permission, every object is assigned an object owner,

who can control how each of these permissions are set, along with

administrators with control levels higher than the object owner.

Furthermore, Active Directory object control and permissions can be

delegated to other users so that they can manage them themselves. At the

enterprise level, this is common because it simply isn't practical for

administrators to be responsible for everyday tasks, such as changing a

password, for thousands of users. Accordingly, delegations can be

assigned to various organizational units to administer other objects and

free up load on the administrator.

1. Object Security Descriptors

Every object within Active

Directory contains a certain amount of authorization data that secures

the object. This information is included in the security descriptor,

which, according to the Microsoft documentation on Active Directory

delegation best practices, includes the following:

Owner

This is the current owner of the object's SID.

Group

This is the SID for the current owner's group.

Discretionary access control list (DACL)

According to Microsoft, this is a list of zero or more ACEs that specify who has what access to the object.

System access control list (SACL)

This is the list of access controls that are used for auditing.

2. Access Control Entities

Access control entities

(ACEs) are Active Directory conventions that give specific permissions

for object access; ACEs are compiled into access control lists and can

take one of six values per ACE:

Allow

Deny

System Audit

Object Allow

Object Deny

Object System Audit

3. Organizational Units

Organizational units

form the basis for a lot of our work as administrators because they are

the most easily mutable form of object collection available. As you

know, OUs can comprise accounts, groups, computers, printers, or various

other objects and can be very robust in their composition. They're

generally implemented for one of two reasons: delegation or Group

Policy.

More often than not,

administrators use OUs for delegation because of how easy they are to

assemble. In fact, they go further than just being easy to use, because

OUs can contain other OUs in what is called OU nesting.

And as OUs nest, they can create more and more complex infrastructures.

Accordingly, on the 70-647 certification exam, a good deal of time is

spent understanding OU design and understanding how to create the OU

hierarchy.

3.1. Organizational Unit Hierarchy

The reason I haven't

covered this in detail up until this point is that in most small

organizations, there really isn't as much of a need for this. Consider a

business with, say, 50 employees. With 50 employees, there is almost no

way that there could be more than 50 organizational units. There may be

the rare case where someone could think up an OU structure that would

make even the most seasoned administrator set down his glasses and say,

"Well, that's a doozy." But more often than not, a small office will

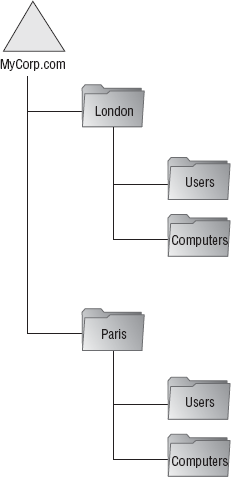

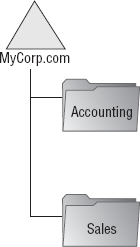

most likely look something like Figure 1.

The design is not very

complex. But imagine you decided to apply this design to an organization

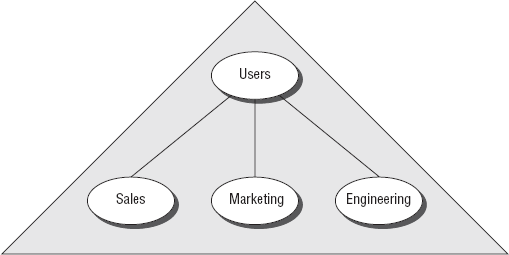

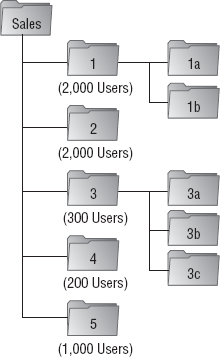

with, say, 10,000 employees. Take a look at what happens in Figure 2, which shows the breakdown of just one OU, Sales.

Can you imagine applying a Group

Policy to the sales group? The chance that all salespeople would need

the same sorts of settings is infinitesimal at best, and moreover, in an

enterprise that scales, you would essentially not have any delegation

opportunities because there simply aren't enough OUs to delegate.

In most large-scale enterprises, OUs are implemented according to four administrative models approved by Microsoft:

Location

Business function

Object type

Hybrid/combination

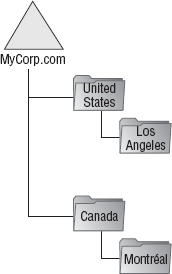

These are, for the most part,

self-explanatory by title. In a location-based OU model, objects are

placed by their location, such as the United States or Canada. Beyond

that, OUs are broken down into more specific locations, such as Los

Angeles embedded within the United States or Montreal embedded within

Canada, as shown in Figure 3.

Within a business

function–based OU, users are divided up based upon their department or

business duties and then divided down further, as shown in Figure 4.

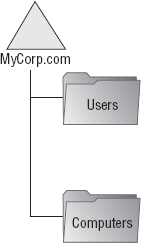

And within an object

type–based hierarchy, objects are separated based upon object

essentials, such as computers, which can then be divided into

workstations and servers, or users, which can be divided down into users

and groups of users, as shown in Figure 5.

And, of course, a

combination OU hierarchy involves the process of combining elements from

either the location, business function, or object type OU and creating a

customized model based on aspects of each of these OUs. For instance,

an OU structure could be separated by location and then be further

refined by object type, as shown in Figure 6.