When it comes to administering a SharePoint farm

using a Web browser, the Central Administration site is an

administrator’s one-stop shop. This holds true for working with

SharePoint’s backup and restore functions in a friendly and interactive

way. In fact, all the backup and restore tools within SharePoint 2010’s

Central Administration site are conveniently organized and can be

accessed through one page within the site.

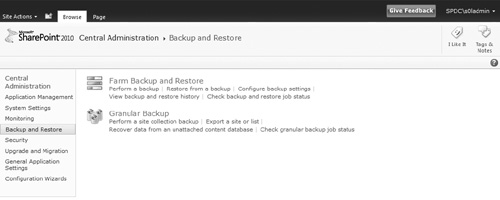

Figure 1

illustrates the primary point of entry to Backup and Restore

functionality within the Central Administration site. For the sake of

simplicity, we refer to this page simply as the Backup and Restore page

for the remainder of the artcile.

You can access the Backup and Restore page through either or both of the following two routes:

Before diving headlong into

Central Administration, you need to know this: the bulk of your true

disaster recovery planning efforts probably aren’t going to revolve

around Central Administration—at least for backup planning. One

limitation that continues to exist with SharePoint’s Central

Administration site is its lack of fundamental scheduling and automation

capabilities. Central Administration is a wonderful tool for

interactively conducting backups and restores, but you cannot script it.

This doesn’t

mean that Central Administration is useless. As this article demonstrates, it’s a fantastic tool for creating targeted, on-demand

backups in an interactive fashion. Many administrators also prefer a

visual interface when restoring data, adjusting backup settings, and

more. Regardless of preferences, you can view the Central Administration

site as simply another tool in your administrative toolbox.

An Overview of Backup and Restore Capabilities

The Central Administration

site allows you to work with SharePoint in a visual and interactive way.

When you cut past the Web pages and links, though, the Central

Administration site is a wrapper around functionality that is exposed

through the methods, properties, and events of key SharePoint

object model types. The differences between Central

Administration and the PowerShell cmdlets have less to do with function

than they do with the form through which their common underlying

functionality is exposed. Both Central Administration and PowerShell

provide different mechanisms and options for carrying out disaster

recovery operations, but they are both employing the same object model

types for the actual grunt work behind the scenes.

Generally

speaking, the backup and restore capabilities of the Central

Administration site fall into two broad categories, and these are

presented to you on the Backup and Restore page as Farm Backup and

Restore and Granular Backup. This article also looks at the special case

of the Configuration-Only Backup, because its intent and usage patterns

differ from what might be considered traditional backup and restore.

Farm Backup and Restore

“Full coverage” is a phrase

that we all like to hear when shopping for insurance, and it is the best

way to think about the capabilities that are supplied through the Farm

Backup and Restore links on the Backup and Restore page. Backups of this

type are commonly called catastrophic backups.

What Catastrophic Backups Include

You’ll often hear

catastrophic backups in SharePoint referred to as “full farm” backups,

but interestingly they really aren’t. Before we get into what isn’t

included in them, let’s talk about the objects that are available for

catastrophic backup, using the SPDEV example farm.

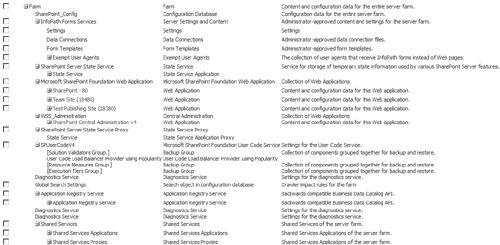

As you can see in Figure 2,

a catastrophic backup is capable of capturing and protecting a variety

of the critical targets within a farm. In general, the targets that can

be captured by a catastrophic backup fall into one of three categories,

and these categories are organized hierarchically.

Farm.

A SharePoint farm is a backup target, and it is normally the backup

target at the top of the hierarchy. In addition to having its own

content (the farm configuration database), the farm is a container for

all other objects that can be targeted for backup within the

environment.

Services and Service Applications.

Many of the platform capabilities that SharePoint provides are driven

by some form of service or Service Application. The Search Service, InfoPath

Forms Services, and Managed Metadata Service are examples that fall

into this category. The information that is captured in a backup of this

type of object differs from Service Application to Service Application,

but it commonly includes settings and any data that is stored in

associated databases.

Web applications.

In the hierarchical sense, Web applications are the children of

SharePoint’s Content Web Service. When targeted for backup, a Web

application carries with it any content databases that are associated

with the Web application. In addition, a backup includes IIS application

pool and binding information, service accounts, alerts, managed paths, web.config

changes (if made through the SharePoint object model or Central

Administration), authentication settings, and sandboxed solutions that

are associated with the Web application.

When a catastrophic backup

is performed through the Central Administration site, selection of any

target automatically includes all subordinate targets in the backup

hierarchy. For example, selecting a Web application automatically

includes all content databases and settings associated with that Web

application. At the highest level in the hierarchy, selecting the

top-level farm target captures all targets within the farm. You cannot

alter this behavior.

Caution

Pay close attention to what is

and is not in a catastrophic backup you perform. If you choose to

perform something other than a full farm catastrophic backup of your

environment, you may unintentionally exclude items that you need for a

successful restore. For example, you cannot back up many Service

Applications without performing a full farm catastrophic backup.

Services and Service Applications that can be backed up individually

often have a service proxy associated with them that does not get backed

up when only the service or Service Application is selected. As another

example, your farm’s configuration database is backed up only when a

full-farm catastrophic backup is executed. These are some of the reasons

for executing full farm catastrophic backups unless you are constrained

by storage space or have a specific selective component backup scenario

you are attempting to address. The contents of a full farm catastrophic

backup are flexible and can be used to restore not only the full farm,

but individual subordinate elements such as specific Service

Applications and content databases.

What It Doesn’t Include

As is common with

insurance, “full coverage” doesn’t come without some fine print that you

need to read and a variety of limitations you need to understand. In

the case of catastrophic backups, “full coverage” is only complete in

the sense that it covers all elements specifically within the boundaries

of SharePoint.

SharePoint

relies heavily on the services and functionality of many systems,

including SQL Server, Windows Server, IIS, and a host of additional

systems. Many of these systems are service providers for SharePoint, but

SharePoint itself isn’t aware (nor should it be) of how these platforms

implement or provide their services. This also means that a SharePoint

catastrophic backup cannot capture settings and data needed to restore

these external systems in the event of a disaster.

Even if you execute a full farm

catastrophic backup, the following are some of the more common settings

and data that backup does not capture:

Application pool account passwords

HTTP compression settings

Time-out settings

Custom Internet Server Application Programming Interface (ISAPI) filters

Domain membership for the server

IP security (IPsec) settings

Network Load Balancing (NLB) settings

Secure Socket Layer (SSL) certificates

Dedicated IP address settings

SharePoint integrated SQL Server reporting and analysis services databases

Manual changes to any web.config file

Decentralized customizations

Just

because a full farm catastrophic backup doesn’t cover these items

doesn’t mean you cannot capture them with a backup.

When it comes to catastrophic backup limitations, a number of additional items are worth mentioning:

Service Application configuration data.

Just because a Service Application is selected for catastrophic backup

doesn’t mean that all of its configuration data is captured. In the case

of the Secure Store Service Application, for instance, a passphrase is

supplied at the time that the Service Application is configured. The

passphrase is used to provide access to a Master Key that is used in the

encryption of credential sets. Backing up the Secure Store Service

Application does not backup the passphrase; you must save and protect

the passphrase when you configure a Secure Store Service Application

instance and have the information available if a restore must be

performed. The Secure Store Service Application is probably the most

common example of configuration information that isn’t automatically

captured, but others may exist. At some point in your backup planning,

you should review each of the Service Applications you use in your farm

and compile information like passphrases, credentials, and other

information that must be tracked and made available for restore

scenarios.

Remote Binary Large Object (BLOB) Storage, or RBS.

SharePoint’s default action is to store images, documents, and other

file types as BLOBs within SQL Server. When BLOBs are stored in content

databases in this manner, they are captured when a catastrophic backup

is run provided the content databases are selected for backup inclusion.

If the SQL Server’s BLOB storage behavior is altered through the use of

an RBS provider other than the FILE-STREAM provider, a catastrophic

backup does not capture BLOB contents when it is run. In such a

situation, you must employ some other form of backup to ensure that all

associated BLOB data is protected.

SQL Server Transparent Data Encryption (TDE).

SharePoint 2010 can perform catastrophic backups of SQL Server

databases that leverage TDE, but SharePoint does not capture the

database encryption key (DEK) and other encryption components during the

process. It is your responsibility to manually back up and restore TDE

components, such as the DEK, a signing certificate, and the private key

associated with the signing certificate. Failure to capture these

components may block your ability to make decrypted data available in

restore scenarios.

Business Connectivity Services (BCS).

BCS is typically employed when SharePoint needs to interact with other

line of business (LOB) data systems such as external relational

databases, customer relationship management (CRM) systems, custom Web

services, and virtually any other non-SharePoint system housing data of

interest. Although a catastrophic backup can capture configuration

information (such as external content type definitions) defining

how SharePoint interacts with these external data systems, it cannot

capture any of the actual business data housed within the systems.

Protection of such data must be pursued separately and represents a

different target or set of targets in the disaster recovery sense.

The preceding list of

items describing what can and cannot be included in a catastrophic

backup is far from the last word. Because you can extend the

catastrophic backup system through custom code and third-party products,

the list of targets that can be covered in your environment could be

larger.

Examining the Catastrophic Backup Files

When you execute a

catastrophic backup, you might be surprised to discover all the folders

and files that are placed in the backup destination. In practice, a

catastrophic backup is far from a straight file generation process.

Understanding the files that constitute a catastrophic backup set can

help you manage those files and aid in your understanding of the backup

process.

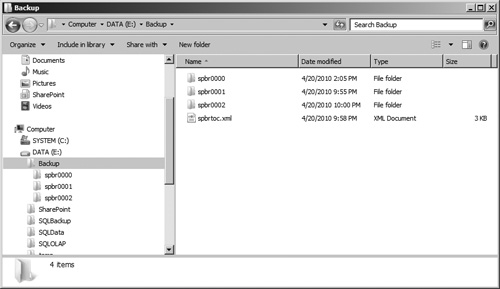

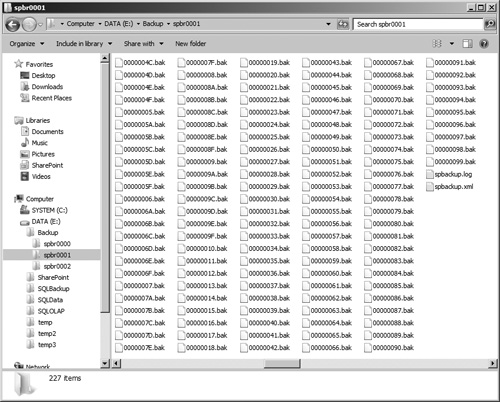

During catastrophic backup execution, the backup set that is generated consists of several files and directories. See Figure 3

for an example of a backup storage directory containing the results of

several catastrophic backup operations. Specifically at the root level

of that location, you find two items related to that completed backup: a

file called spbrtoc.xml and at least one directory named spbrNNNN. (NNNN designates a sequential four-digit hexadecimal number that SharePoint uses as a unique numeric identifier for your backup files.) SharePoint automatically increments the NNNN number as you save additional backups to this directory, starting at 0000.If you change your target backup location to a new directory, SharePoint starts the numeric identifier back at 0000. spbrtoc.xml is an XML file storing the history information for the catastrophic backups stored in the target file location.

Note

spbrtoc.xml’s file

name is an acronym for SharePoint Backup Restore Table of Contents. If

you change your target backup file storage location in the future,

SharePoint creates a new spbrtoc.xml in that location as well.

Caution

Avoid manually

updating or modifying the files in your catastrophic backup set. This

action can potentially corrupt your backup files and lead to problems

during a restoration. Microsoft does not support writing to, moving,

deleting, or renaming any of the files in a SharePoint catastrophic

backup set.

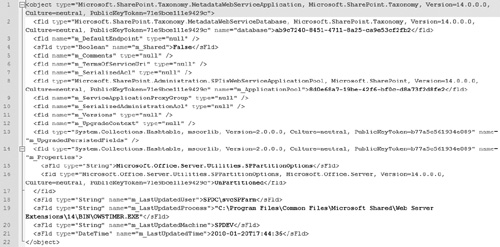

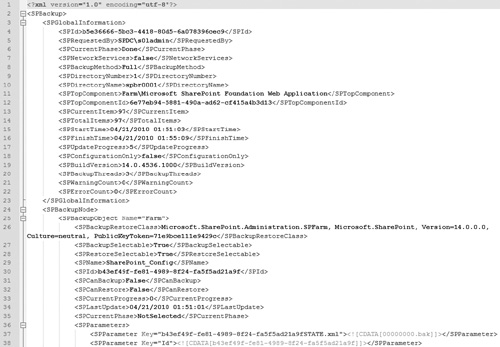

spbrtoc.xml (shown in Figure 4) contains SPHistoryObject children under the top-level SPBackupRestoreHistory element. One SPHistoryObject appears for each catastrophic backup set stored in the backup location, and the SPHistoryObject elements are ordered from most recent to oldest. The spbrtoc.xml

file also contains entries for each restore operation run using the

catastrophic backup sets that are stored in the backup location. Each SPHistoryObject contains the following child elements describing the backup set:

SPId. This is a globally unique identifier (GUID) that SharePoint generates automatically for the backup set.

SPParentId. If the SPHistoryObject is the child of another SPHistoryObject,

this element is present and populated with the SPId GUID of the parent.

This element typically ties a differential backup to its parent full

backup.

SPRequestedBy. Displayed in DOMAIN\User format, this is the SharePoint administrator who submitted the backup request.

SPBackupMethod. Options are Full or Differential.

SPRestoreMethod.

Options are None, Overwrite, or New. None indicates that the backup has

not yet been restored. Overwrite indicates that the Same Configuration

option was used to restore the backup, and New similarly maps to the New

Configuration restore option.

SPStartTime.

This is the date and time that the backup process was initiated,

displayed in MM/DD/YYYY HH:MM:SS format. The time is displayed in

Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), not the local time zone of the server.

SPFinishTime.

This is the date and time that the backup process completed, displayed

in MM/DD/YYYY HH:MM:SS format. The time is displayed in UTC, not the

local time zone of the server.

SPIsBackup.

Options are True or False. If the entry in the file is for a backup,

this value is True. If the entry is for a restore, this value is False.

SPConfigurationOnly.

Options are True or False. When both content and configuration settings

are backed up, this value is False. If configuration settings are

backed up without content, this value is True.

SPBackupDirectory. This is the Universal Naming Convention (UNC) path to the folder containing the files that make up the backup set.

SPDirectoryName. This is the name of the folder (relative to the spbrtoc.xml file) containing the files for the backup package.

SPDirectoryNumber. This is the sequential number assigned to the backup package. The first package in the directory has a value of 0 (zero).

SPTopComponent.

This is the top-most component in the tree view hierarchy of the backup

component selection page that was checked as a target for backup.

SPTopComponentId. This is the GUID that internally identifies the SPTopComponent.

SPWarningCount. This is the number of warnings generated during the backup process.

SPErrorCount. This is the number of errors generated during the backup process.

Within each catastrophic backup set’s specific SPBackupDirectory (see Figure 5 for an example), SharePoint creates numerous files that represent your selected backup targets.

Every directory contains the following elements:

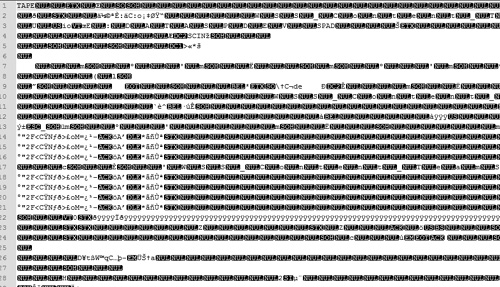

One or more .bak files.

These files contain the contents of your selected backup components

that come from a combination of the SharePoint farm and the SQL Server

databases. Figure 6 shows an example of the more human-readable .bak files containing serialized SharePoint object data. The other type of .bak

file that is written to the directory contains SQL database backup

information. SQL Server backup files contain binary data that begins

with a recognizable TAPE marker, as shown in Figure 7. Beyond the TAPE marker, though, the contents of the file aren’t readable.

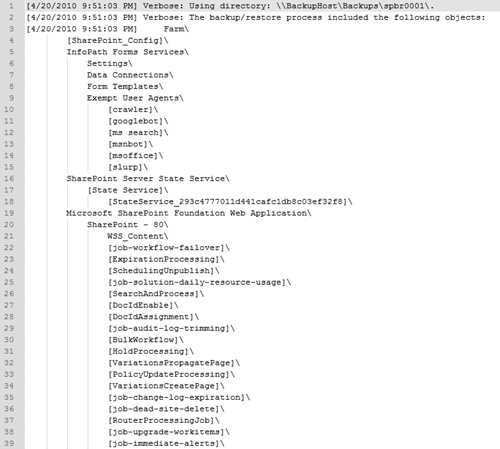

spbackup.log.

This text file contains the details of what occurred during the backup

operation that generated the associated catastrophic backup set. Figure 8 shows an example of an spbackup.log file.

Note

All

time stamps in this file are saved based on the local time zone of the

server hosting the Central Administration site, not UTC.

spbackup.xml.

This XML file contains all the metadata and settings information that

was collected for each of the farm backup targets during execution of

the catastrophic backup. Figure 9 shows an example. Each file contains a single SPGlobalInformation node that contains data on the overall backup, similar to the package’s SPHistoryObject data in its associated spbrtoc.xml file. Below the SPGlobalInformation element appear many SPBackupNode

elements for each of the farm components targetable by catastrophic

backup operations—not just the ones that were selected for backup. Upon

completion of the backup, SPBackupNodes that were actually selected for backup have a descendent SPCurrentPhase element value of Done. Those that were not included in the backup have an SPCurrentPhase element value of NotSelected. The SPBackupNode elements are hierarchically nested to reflect the relationships that exist between the components associated with each element.

In some situations,

SharePoint may create additional files within the backup set’s directory

depending on the components selected for backup or subsequent actions

that are taken with the backup set:

One or more folders with GUIDs for names. Folders of this type appear if one or more Search Service Applications were targeted for backup. Within these folders exists a Config directory containing noise and thesaurus files and a projects directory containing the backed up Search indices for your environment.

sprestore.log.

SharePoint generates this text file if you have used the catastrophic

backup set for restore operations. The log file contains the details of

what occurred during the restore process using this backup package.

sprestore.xml. This file is similar in content and purpose to spbackup.xml—the main difference being that it is associated with a restore operation and not a backup.

Note

All time stamps in these

files are saved based on the local time zone of the server hosting the

Central Administration site, not UTC.

When You Should and Shouldn’t Use It

A full farm catastrophic

backup offers the greatest degree of coverage for your farm of any

out-of-the-box tools. This makes a full farm catastrophic backup the

operation of choice anytime you plan to introduce significant changes

into your SharePoint environment. The following operations are just a

few examples of those that are more comfortably performed knowing that

some catastrophic backups have been taken for insurance against

unexpected problems or failures:

Application of a service pack or hotfix

Changes to farm topology or the farm environment, such as the addition of a new farm member or the relocation of a server

The addition and deployment of a new solution package (WSP) within the farm

Any operations that result in significant changes to content databases, such as site collection relocation using the Export-SPWeb and Import-SPWeb PowerShell cmdlets

In most cases, it is

desirable to capture a catastrophic backup both before and after the

operation being performed. Why two backups? Well, the backup that is

captured before the change provides you with a catastrophic backup set

that is stable and consistent. You can use it to roll back the farm or

its elements in the event of failure following the change.

After you have made the

change and verified that the farm is in a stable and consistent state,

you should take another catastrophic backup. This backup set provides a

new baseline for the farm going forward. This is not immediately useful

within the context of the change you made, but it is important in that

the backup becomes the first known stable and consistent point in the

farm following the change. This is important because it gives you a

fall-back point until you make the next major change to your

environment. At that point, the backup/apply change/backup sequence just

described is repeated.

There are certainly times

when you should avoid a catastrophic backup. Executing a catastrophic

backup, particularly a full farm catastrophic backup, can place a

significant load on your SharePoint infrastructure. This load can

adversely impact an end user’s experience and other operations within

your farm. As a responsible administrator, you should consider capturing

performance metrics during catastrophic backups as they are being

performed if you don’t have a solid understanding of how such backups

impact your farm. Observing SharePoint and SQL Servers to see how their

memory, disk, and network utilization are affected can help you make

informed decisions regarding when catastrophic backups can or should be

run. As a general rule of thumb, run catastrophic backups during off

hours or times of low SharePoint use whenever possible.

SharePoint’s catastrophic

backups can also consume a lot of disk space, and the platform includes

no built-in mechanism to prune or manage backup storage. If your disk

space is constrained or you spend less time managing your storage space

than you would like, you should probably think twice about frequent use

of catastrophic backups.