The basic concepts associated with backup and restore

operations are easy to understand. Backups capture data, and restore

operations put that data back. The devil is always in the details,

though, and this is especially true with SharePoint’s backup and restore

capabilities. Before attempting any form of backup or restore with

SharePoint, you need to check a number of line items in a rather lengthy

checklist.

The good news is that once you

have configured your environment properly for backup operations, there

is little else that you must configure to successfully conduct restore

operations.

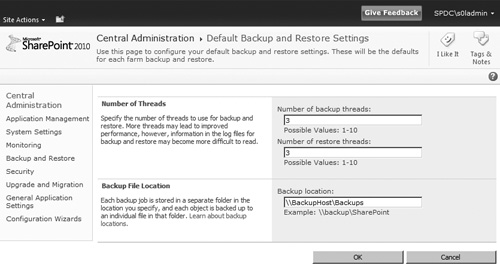

Backup Settings

Only a handful of high-level

settings exist for configuration of catastrophic backup and restore

operations within Central Administration, and you access these through

the Configure Backup Settings link on the Backup and Restore page.

Clicking this link takes you to the BackupSettings.aspx page, as shown in Figure 1.

Number of Threads

SharePoint 2010 gives you

control over the number of threads that are spun-up to carry out both

catastrophic backup and catastrophic restore operations. By default,

each of these operations is configured to utilize three threads during

execution.

If you aren’t familiar

with threading, it is easiest in this scenario to equate a thread with

an object that is being backed up or restored. Specifying three backup

threads, for example, roughly translates into three objects being backed

up in parallel during the execution of the backup operation. Three

restore threads, on the other hand, means that three objects at a time

can be restored

simultaneously. The greater the number of threads of execution, the

greater the degree of parallelism and the faster you can potentially

process your objects for catastrophic backup or restore.

So, what is to stop you from

dialing your backup and restore threads up to their maximum value of 10?

First of all, there is the obvious warning on the BackupSettings.aspx

page indicating that it could become difficult to interpret the log

files that are generated during the backup and restore operations. With

10 concurrent writers to a single file, the contents are bound to appear

jumbled.

More important than

jumbled log files, though, is the potential impact that 10 threads of

parallel execution carries with regard to server resources. Processing

10 objects at once puts a significantly greater strain on the memory,

CPU, and disk resources of your SharePoint servers than processing only 3

objects at a time. In addition, streaming backup or restore data for 10

objects at once across a network places a greater load on your

infrastructure if it is involved in the equation. At the extreme, this

extra load could simply cause thrashing at one or more bottleneck points

on your servers and infrastructure, leading to poorer overall

performance instead of better.

As with most dials, some amount

of experimentation is required to find the sweet spot that allows you

to maximize your catastrophic backup and restore performance without

unintended side effects. Consider running multiple backup and restore

operations as a test, and vary only the number of threads in use for

each one. While conducting these tests, pay attention to the memory,

CPU, and disk load being placed on each server and infrastructure

component that is involved in the backup or restore operation. Once you

have found settings that offer the desired balance of performance and

system load, lock them in and document them. Remember, too, that

settings are specific and relevant only to the environment in which they

were tested and measured.

Backup File Location

Your choice of

catastrophic backup location is an important one. Microsoft recommends

that you use local disks whenever possible for maximum performance, and

this recommendation is easily observed when all elements of the

SharePoint farm, including SQL Server, are installed on a single

physical or virtual server. In the case of an all-in-one server, local

drive references for both SharePoint and SQL Server point to the same

location on the drive-mapped storage medium.

For most

practical purposes, multiserver SharePoint farms that intend to leverage

SharePoint’s catastrophic backup and restore capabilities must be able

to reach a network share that is accessible through a UNC path

specification. Microsoft also suggests that network shares with 1

millisecond or less of latency between themselves and the SQL Server(s)

housing SharePoint content should perform well.

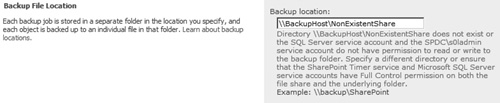

When you select a backup file location on the BackupSettings.aspx

page, SharePoint doesn’t help you with any of the latency-related

issues described thus far. SharePoint does, however, notify you of

problems and potential remedies if you try to specify an invalid

location, as shown in Figure 2.

You

can only accept changes by clicking the OK button after valid settings

have been supplied. If valid settings cannot be supplied, the only

option is to click Cancel.

Services, Accounts, and Permissions

The execution of

backup and restore operations through Central Administration engages

quite a few moving parts. Each time one of these operations is

attempted, a number of different services, file locations, and security

contexts end up in the mix. Understanding the interactions of these

elements is essential to proper backup configuration and

troubleshooting.

Understanding the Security Context

The key to

understanding backup and restore operations that are initiated through

Central Administration is realizing that little actually happens within

the security context of the currently logged-on administrator. Instead,

administrators configure and prepare operations, such as a backup, that

are then handed off to other services for execution. The following list

of actions roughly represents the steps that are carried out when a full

farm catastrophic backup is run:

1. | You, the administrator, specify the parameters of the backup operation.

|

2. | A SharePoint Timer service backup job is created and scheduled for one-time execution using the settings you specified.

|

3. | During

a sweep, the Timer service begins execution of the backup job and

engages SQL Server for some of the required backup operations.

|

4. | Both the Timer service and SQL Server write directly to the designated backup area to carry out the backup.

|

5. | Upon completion, SQL Server is disengaged and the Timer service backup job completes.

|

6. | The backup is finished.

|

In the execution of the

previous steps, the only step that actually occurs within your

administrative account context is step 1. Each step after the first one

occurs within the context of a service account. Timer service actions

are carried out in the context of the SharePoint farm database

access account—the same account that is used as the Central

Administration site’s IIS application pool identity. SQL Server actions

are carried out in the context of the account under which the SQL Server

database engine is running. This differs significantly from the backup

and restore operations that are carried out through PowerShell, where

your administrative account context is the one that is primarily

utilized for SharePoint operations.

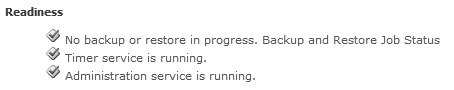

Services and Their Accounts

Ensuring that the

appropriate services are enabled and possess the necessary privileges to

carry out backup and restore tasks can be tricky. Thankfully, Central

Administration provides some useful guidance to ease the burden of

configuration in this area. At the top of each backup and restore

application page within Central Administration is a Readiness area. For

each backup and restore operation exposed, Central Administration alerts

you to the services that need to be running and their current state of

readiness for the desired operation. Figure 3 illustrates the Readiness area when a catastrophic backup operation is selected and you are directed to the Backup.aspx page.

If either the Timer service or the Administration service isn’t started when you navigate to the Backup.aspx

page, you receive a warning and a red exclamation mark instead of the

check mark for the affected service(s). You can continue your

configuration of the backup operation, but attempts to start a backup

without addressing the Readiness warnings result in an error and

failure.

Note

Readiness warnings

identify the Timer service as the Microsoft SharePoint Foundation Timer

2010 service and the Administration service as the Microsoft SharePoint

Foundation Administration 2010 service. If you attempt to locate

services with these names in the Microsoft Management Console (MMC)

Services snap-in, you won’t find them. In reality, these services appear

in the Services snap-in as the SharePoint 2010 Timer service and the

SharePoint 2010 Administration service, respectively.

In addition to the

aforementioned services running, you need to address a couple of

permission issues before carrying out a catastrophic backup or restore

operation. As mentioned in the full farm catastrophic backup example

earlier, both the SharePoint Timer service and the SQL Server service

read from and write to the backup file location you specify. For these

services to carry out their

duties, the accounts that the SharePoint Timer service and SQL Server

service run under must have Full Control permissions on the backup file

location for catastrophic backup and restore operations. If one or both

of the accounts that are associated with the services lack the

permissions they require on the backup file location, your requested

operation will fail.

Note

If your SQL Server service

is configured to use one of the built-in accounts such as Network

Service, be aware that SQL Server presents itself to network resources

using the machine’s computer account—not a separate domain user account.

The access requirements are

slightly different in the case of Granular Backup and Restore

operations. Each of these operations is carried out by the SharePoint

Timer service alone. SQL Server is not involved, so the rights of the

SQL Server service account aren’t a factor. For Granular Backup and

Restore operations, only the SharePoint Timer service must have Full

Control permissions on the backup file location.

User Accounts

Even though Central

Administration hands off the actual execution of backup and restore jobs

to service accounts, there are still some rights that you, the

administrator, require to access and carry out the necessary

configuration steps.

Granular Backup.

To access Granular Backup functions, you require nothing more than

membership in the Farm Administrators group. If you aren’t a member of

the Farm Administrators group, it is generally pretty obvious because

you can’t access Central Administration.

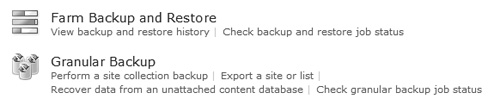

Farm Backup and Restore.

The catastrophic backup and restore functions that are available within

Farm Backup and Restore require that you are a member of the local

Administrators group on the server housing Central Administration. If

you are not a member of the server’s Administrators group but are a

member of the Farm Administrators group, a couple of the Farm Backup and

Restore functions are still available. As Figure 4

illustrates, though, the critical links to access backup, restore, and

settings configuration pages are removed via security trimming.

Full Backups Versus Differential Backups

One

of the options that is available to you when you are preparing a

catastrophic backup is whether to perform a full backup or a

differential backup. A full backup performs a complete backup of all

objects you select, whereas a differential backup only performs a backup

of the selected objects that have changed since the last full backup.

By extension, this means that differential backups tend to be smaller

than full backups—an attractive consideration if you are trying to make

the most of your investment in disk storage.

As stated, differential

backups only capture changes that have been made to the selected objects

since the last full backup. For differential backups to work, a full

backup of the selected objects must exist as a point of comparison to

identify what has changed. Without a full backup as a point of

comparison, you cannot perform differential backups. If you attempt to

create a differential backup without first having taken a full backup,

SharePoint simply throws up an informative error and aborts the

operation.

Caution

When mixing and matching

full and differential backup types, we have a simple recommendation: the

first backup created in the file backup location should be a full farm

catastrophic backup. If you begin with a full farm catastrophic backup,

you can subsequently execute a differential backup of any farm object

(including the full farm) without fear of potential problems or loss.

You can run into trouble if you try the opposite scenario, such as

executing a full backup of only a Web application followed by a

differential backup of your entire farm. SharePoint allows you to

execute this sequence of backup operations without error, but subsequent

catastrophic backups, whether full or differential, never capture more

data than just the original Web application until you perform a full

backup of greater scope. This scenario can be confusing and result in

unintentional data loss if you mistakenly expected the second full farm

differential backup to contain data for more than just the Web

application that was originally captured.

Using Unattached Content Databases

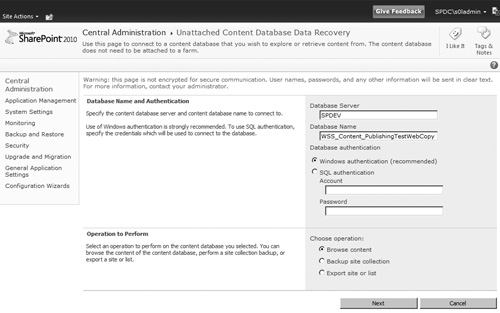

Another interesting

addition to the toolbox of Central Administration capabilities in

SharePoint 2010 is the ability to browse and recover data from

SharePoint content databases that are not attached to the farm, as shown

in Figure 5.

The UnattachedDbSelect.aspx page shown in Figure 9.15

is the entry point to working with unattached content databases, and

you can access it easily from the Backup and Restore page through the

Recover Data from an Unattached Content Database link. From this area,

it is possible to browse a content database, back up a site collection

within the content database, or export content directly from the

database.

To understand why this

feature is so powerful, you must first understand some of the

constraints of content databases and how recovery operations from them

were handled in the past.

Content Recovery Prior to SharePoint 2010

This

article spends a great deal of time discussing how to handle

catastrophic backup and restore scenarios, but in reality catastrophic

farm failures occur infrequently. On a day-to-day basis, administrators

more commonly find themselves faced with the problem of content loss in

some limited form. Whether through error, unintended or accidental site

deletion, or some other set of circumstances, users lose content from

within their SharePoint sites. This type of loss doesn’t constitute a

catastrophic failure; nonetheless, there is a real need for some type of

recovery from a catastrophic backup of the content database that housed

the content prior to its deletion or loss.

With SharePoint 2007, this type

of recovery scenario presented some specific challenges. In most of

these content recovery scenarios, the desire wasn’t to replace the

entire content database from backup. The goal was to simply recover a

specific item, list, site, and so on that had been deleted. These

object-level recovery scenarios were possible, but they were difficult

with SharePoint’s native backup/recovery and export/import tools.

Without additional tools, you commonly executed such a recovery

according to the following series of steps:

1. | You, the administrator, were notified of the lost content and asked to recover it from backup.

|

2. | You

needed to locate a backup of the content database that contained the

lost content. The backup could take the form of a SharePoint

catastrophic backup, a SQL Server database backup, or something else

entirely.

|

3. | You

restored the content database to a separate recovery farm

environment—or at least a farm that was not the current production farm.

|

4. | After

attaching the content database to a Web application in the recovery

farm, you located the object to be recovered and exported it. Such an

export was typically conducted through an STSADM.exe –o export operation.

|

5. | The export package that was generated from step 4 was copied to the production farm environment.

|

6. | In the production farm environment, the export package was imported to the appropriate site or other container using an STSADM.exe –o import operation.

|

7. | The recovered content was available for users once the import operation completed.

|

The greatest pain in this

sequence of steps typically centered on the recovery farm requirement

described in step 3. Why was an entirely separate SharePoint farm needed

just to recover some content? The answer, quite simply, is because two

copies of the same content database cannot be attached to the same

SharePoint farm at once. Every content database in SharePoint possesses a

GUID that differentiates it from all other content databases. If you

attempt to attach a content database possessing a specific identifier to

a farm where a database with that same identifier is already attached,

the operation fails.

In the case of a content

database that was restored from backup under SharePoint 2007, it wasn’t

possible to leverage the SharePoint object model (including the

functionality within the Content Deployment API that is needed for the STSADM –o export

operation) to recover objects from the database without first attaching

that database to a farm. The option to first detach the existing

content database from the production farm was always a possibility, but

it involved taking down all site collections housed in the target

content database—not just the site collection that was tied to the

content recovery operation. In most cases, the practical response to

these constraints was the use of a separate farm for recovery purposes.

Content Recovery Improvements in 2010

SharePoint 2010 simplifies

content recovery efforts tremendously by allowing you to work with

content databases and perform object model operations against those

databases without requiring that the databases are attached to a

SharePoint farm. This means that a recovery farm is no longer needed,

because SharePoint 2010 can continue to work with a production content

database that is attached to the farm at the same time it is exporting

content from an unattached copy of the same content database that was

restored from backup. In short, two copies of the database are present

in SQL Server, but only one of them is actually attached to the

SharePoint farm.

Note

For

the record, there isn’t anything stopping you from using the unattached

database recovery capability to back up or export data from a normal

production database that is actually still attached to the farm. This

capability is redundant with the site collection backup and content

export functions that are built into Central Administration, though, so

an actual usage scenario involving unattached recovery from an attached

database is left up to your imagination.

Removing the need for a

recovery farm obviously saves you the cost and overhead associated with

the maintenance of an additional SharePoint environment. It depends on

your specific needs and SharePoint environment, but the unattached

content database recovery capabilities of SharePoint 2010 may also allow

you to meet more aggressive recovery time objectives (RTOs) for content

restore operations. With SharePoint 2007, recovery farms were commonly

built as virtualized environments that lacked the processing power and

resources of their associated production environments. A fair amount of

time during content recovery operations was spent locating backups,

moving them between environments, patching the recovery environment to

an equivalent or greater version than production, and other “busy work”

tied to the second farm environment. With the ability to execute a

database restore and content recovery in one farm environment, much of

that extra time and overhead goes away or is at least reduced.