Each of the custom approaches discussed thus far has its own unique set of advantages and disadvantages. The types within the Microsoft.SharePoint.Administration, Microsoft. SharePoint.Administration.Backup, and Microsoft.SharePoint.Deployment namespaces offer a variety of built-in capabilities for preserving and recovering content and other important SharePoint

data within your farm. VSS is a proven technology that gives you a way

to generate consistent point-in-time snapshots for the overwhelming

majority of the SharePoint configuration and content data in your farm.

In many cases, some combination of these technologies and code

approaches will prove adequate for your needs.

We clearly recognize

that the approaches discussed thus far may only get you part of the way

toward achieving your ultimate goal. Just as there is no

one-size-fits-all approach to SharePoint disaster recovery, so too is

there no master set of custom code that can solve every backup and

restore need.

The two sections that

follow offer a couple of additional techniques you may use to tackle

aspects of your custom disaster recovery development needs. Neither of

the techniques is specific to disaster recovery development, but both

can be leveraged in a variety of custom development scenarios tied to

SharePoint disaster recovery.

Object Model Walking

If your custom development

scenario is focused on capturing a variable set of content within the

SharePoint environment, particularly at the site collection or subsite

collection level, the idea of object model walking may be of interest to

you.

At a basic level, object model walking

is a general term for traversing hierarchically organized groups of

objects (an object graph) to conduct some operation on them or extract

information of interest from them. For purposes of capturing and

protecting data in SharePoint, you might apply this concept to save or

restore data of interest within a site collection and some subset of its

subordinate objects. In essence, this is how SharePoint’s own Content

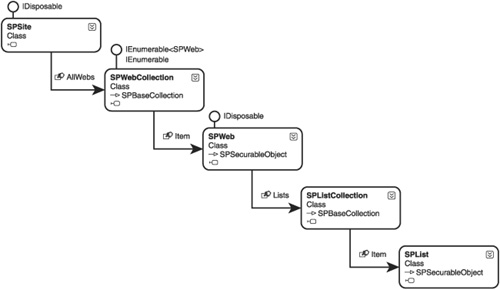

Deployment API is built. Figure 1 demonstrates a selective hierarchy of types that span from the site collection level (SPSite) down to the SharePoint list level (SPList).

Although the Content

Deployment API provides you with mechanisms for exporting from and

importing to a SharePoint site collection, you are bound by the API’s

constraints and modes of operation. These are adequate in most cases,

but they may fall short in others. Consider the case of workflows, for

example. Data that is acted on by workflows is relatively

straightforward to capture, but the state of the workflows is not. The

Content Deployment API doesn’t allow you to capture or export workflow

state.

If the Content Deployment API

proves to be more of a barrier than a building point, you may decide to

avoid it altogether and come up with a custom mechanism for protecting

all the data of interest. If you elect to protect site collections and

their data, you would likely start by examining the site collection (SPSite)

of interest to read and capture all the data of interest that is

represented by it—workflows, work items, users, permissions, recycle bin

information, activated features, and more. The list is extensive. Some

objects and properties can be read directly, whereas others require the

use of helper objects or predefined access sequences.

Of course, the SPSite is just the tip of the iceberg. Each SPSite contains at least one SPWeb object in the form of the RootWeb, and in all likelihood the SPSite instance contains many more SPWeb objects that are organized below it in a hierarchy. These SPWeb

objects also have their own properties and collections of objects that

require processing. Some of the data can be cleanly extracted and

reconstituted into object form later, but many of SharePoint’s objects

can’t be created or manipulated outright; they possess constraints,

dependencies, and logic that require careful orchestration to arrive at a

point where a reconstituted object matches the state that existed at

the time its original object was persisted.

Ultimately, the amount of data

and the fidelity with which it is captured is a decision that is left

completely up to you. Also left up to you is the manner in which you

read, persist, load, and reapply the content you are protecting. There

is no predefined way to translate SPSite, SPWeb,

and dependent objects for storage with the call of a single method. At

the same time, re-creating those objects in a usable form from your

storage is going to prove challenging.

If you’re thinking

that this approach to content protection sounds like it could be an

awful lot of work, you’re absolutely right. The amount of work is tied

to the fidelity with which you intend to capture and restore data. A

full-fidelity backup codebase that is based on object model walking is

certainly possible, but it would be a complex undertaking. Object model

walking in your own code is most appropriate when you are trying to

capture either a limited subset of Share-Point data or data that isn’t

captured through the catastrophic and deployment types.

Employing Serialization Surrogates

Serialization

surrogates aren’t specific to SharePoint, nor are they a new concept to

.NET development. They come in handy, though, when you want to

serialize class instances that you don’t control the source for. To

understand why this is applicable in the case of protecting SharePoint

data, you need to have some familiarity with SharePoint’s history and

how it works under the hood.

Under the Hood with SPRequest

Although SharePoint 2010 comes

with a rich object model you can employ to address all manner of custom

development challenges, it has a dirty little secret—underneath its

managed library hood, SharePoint runs on an engine that has a

significant chunk of COM in it. Digging into the Microsoft.SharePoint.dll and the Microsoft.SharePoint.Library namespace reveals the SPRequest type. The SPRequest type is the managed wrapper around a wealth of methods that are exposed by the OWSSvrLib.dll dynamic link library. The majority of the functionality that is exposed to .NET callers in the SPRequest type gets mapped directly through to unmanaged methods in the OWSSvrLib.dll COM library.

You might be wondering why the SPRequest

type is so special and merits the mention that it’s gotten so far. It

would be a fair question, and the answer is pretty straightforward. Two

of the most common types you use when working with SharePoint content

are backed by the SPRequest type. Those two types are SPSite and SPWeb. Without SPSite and SPWeb, the options for working with content in SharePoint grow slim pretty quickly.

Serialization Challenges

You might recall from the “Object Model Walking”

section that data protection schemes based on object model walking are

often challenging due to issues of persistence. Protection of

Share-Point content revolves around the SPSite and SPWeb

types, and both of these types contain a dizzying array of properties,

methods, and associated collections. The object model graphs that begin

with these types are typically deep, complicated, and span the boundary

between managed and unmanaged code.

In most areas of .NET

development, deep and complicated object graphs like the ones described

are routinely dealt with using serialization types and techniques. Serialization is the process of converting an object graph into a form that can be stored or transmitted, and deserialization

is the complementary process of converting the stored or transmitted

form back into a usable object graph. Binary serialization of objects in

.NET is typically handled by the types residing in the System.Runtime.Serialization

namespace, but binary serialization isn’t the only type available to

.NET developers. XML serialization is common, as well, and is typically

used in areas such as Web service communications.

Because serialization is commonly used to persist object graphs, you might be wondering why it wasn’t mentioned in the “Object Model Walking” section. Unfortunately for SharePoint developers, SPSite, SPWeb, and many of the other types that are tied to site collection content aren’t good candidates for straight serialization.

The easiest way to grant a class serialization support via .NET’s built-in serialization types is to adorn it with the [Serializable] attribute. This won’t work for the SharePoint types, though, because you don’t control the source code for those types.

SPWeb and SPSite

aren’t sealed objects, so technically you could subclass them to create

your own derived types and control the serialization behavior through

the subclasses. This approach is less than desirable, though, because at

their core the SPWeb and SPSite

types simply weren’t designed to be serialized given their COM origins.

In addition, integrating your custom derived types with other (native)

SharePoint types, methods, and properties would prove problematic at

best—if possible at all.

Although direct serialization support for SharePoint types is likely a dead end, there is an alternative.

Serialization of SharePoint Types via Surrogate

The .NET Framework supports the

use of serialization surrogates when you want to serialize and

deserialize objects that weren’t originally designed to support these

activities. A serialization surrogate is a separate class that understands a specific nonserializable type (like the SPSite

type) and can act as a stand-in when serialization requests are made to

serialize or deserialize instances of the nonserializable type.

To better illustrate this concept, examine the activity diagram shown in Figure 2 for the series of steps that are carried out when .NET is called upon to serialize an object.

The branch of the diagram marked

by a circled number one shows the path that is followed when objects

that have a surrogate are serialized. The path marked by a circled

number two shows serialization under nonsurrogate conditions.

The primary benefit of

serialization surrogates when working with SharePoint objects is the

fact that the SharePoint objects themselves are really only passed as

data for the surrogates to operate upon. The actual data that is written

out for serialization is left up to the surrogate. Although this is

conceptually similar to the straight object model walking scenario

presented earlier, you should bear in mind that there isn’t a need to

create all the custom persistence plumbing and infrastructure in the

same way that you would have to in the object model walking case. In

addition, surrogates support a number of advanced scenarios, such as

surrogate selector chains and type remapping during deserialization,

that make them worthy of consideration in custom persistence scenarios.