When you install an operating system, the Setup

program includes default configuration settings for security features;

these settings might or might not be suitable for your needs. When you

create a secure baseline installation for your computers, you have to be

familiar with the operating system’s default security settings,

understand the effects of those settings on your overall security

strategy, and determine whether you want to change them on your

computers.

Evaluating Security Settings

Windows Server

2003 and Windows XP Professional are the current operating systems that

Microsoft has designated for use on network servers and clients.

Security was a major concern to their designers, and the systems contain

many configurable security features. The following sections examine

some of these features and their default settings and discuss how to

manipulate these settings to modify the security of your baseline

installation.

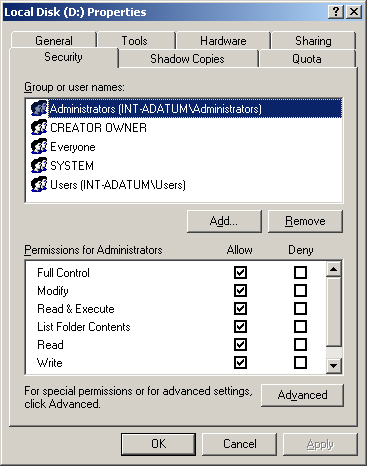

File System Permissions

File system permissions

constitute one of the basic security tools in any network operating

system; one that network administrators are likely to use every day.

Access permissions are a feature of the Windows NTFS file system that

enables you to specify which users and groups are given access to a

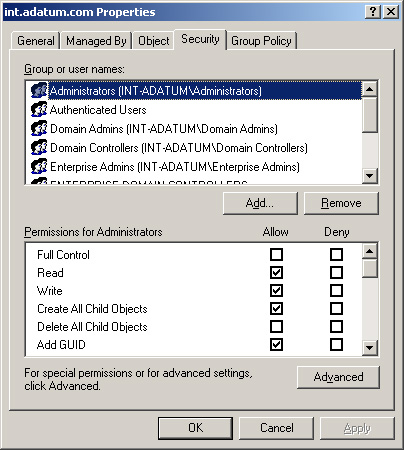

specific folder or drive and what degree of access they have. To modify

the permissions for a drive or folder, you display its Properties dialog

box, and then click the Security tab (see Figure 1).

When you install Windows Server 2003 or Windows XP Professional on a

network that uses Active Directory and format the system drive using

NTFS, the Setup program automatically assigns the file system

permissions shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Default Windows File System Permissions for System Drive

| | System Drive (Root) | Documents And Settings Folder | Program Files Folder | Windows Folder |

|---|

| Administrators | Full Control | Full Control | Full Control | Full Control |

| Users Group | Read & Execute | Read & Execute | N/A | N/A |

| | List Folder Contents | List Folder Contents | | |

| | Read | Read | | |

| | Create Folders / Append Data | | | |

| | Create Files / Write Data (in subfolders only) | | | |

| Everyone Group | Read & Execute (in root only, not subfolders) | Read & Execute | N/A | N/A |

| | | List Folder Contents | | |

| | | Read | | |

| Authenticated Users Group | N/A | N/A | Read & Execute | Read & Execute |

| | | | List Folder Contents | List Folder Contents |

| | | | Read | Read |

| Server Operators Group | N/A | N/A | Modify | Modify |

| | | | Read & Execute | Read & Execute |

| | | | List Folder Contents | List Folder Contents |

| | | | Read | Read |

| | | | Write | Write |

Caution

File

system permissions are available only when you format your computer’s

drives using NTFS. If you format your drives using the FAT file system,

there are no permissions and all users have full access to the drive. |

As you can see in the

table, the Windows operating system assigns almost all file system

permissions to groups, not to users, which makes the task of managing

permissions much easier. Not surprisingly, the Windows operating system

assigns the Administrators group the Full Control permission over the

entire drive, enabling members of this group to perform any action on

existing files and folders, as well as create new ones. The Windows

operating system grants the members of the Users group permission to

read and execute files anywhere on the drive, but Users members cannot

modify or delete existing files or folders anywhere except in their home

folders. Users can create folders and write to files in those home

folders, which makes it possible for them to install applications. The

Everyone group receives only the ability to execute, list, and read

files.

Note

In

addition to the permissions in the table, the Windows operating system

grants each user the Full Control permission for the subfolder named

after that user in the Documents And Settings folder. This is the

location of the user’s profile and home folder. |

Off the Record

Technically

speaking, groups like Authenticated Users and Everyone are not really

groups at all, in the accepted sense of the word; instead, they are

called special identities.

Although you can choose a special identity group when you are assigning

permissions, you cannot manage the group in the usual manner. The

Windows operating system creates the special identity groups

automatically, and you cannot delete them or modify their member lists.

The Windows operating system also creates a number of Built-in groups,

such as Administrators and Users, but these are actual groups that you

can modify or delete. |

The Server Operators

group is intended for system support personnel who need more access to

the file system than normal users, but who are not yet trusted with the

Full Control permission. Server operators have full access to the key

Program Files and Windows folders. Their only limitation is that without

the Full Control permission, they cannot grant their permissions to

other users.

Warning

If

you have NTFS drives other than the system drive on the computer

running a Windows operating system, the Setup program does not create

any special permissions there. The program grants the Everyone group

Full Control over the entire drive, so that anyone can perform any

action, including modifying or deleting existing files. It is up to the

administrators to implement a system of permissions on these drives once

users have populated them with files and folders. |

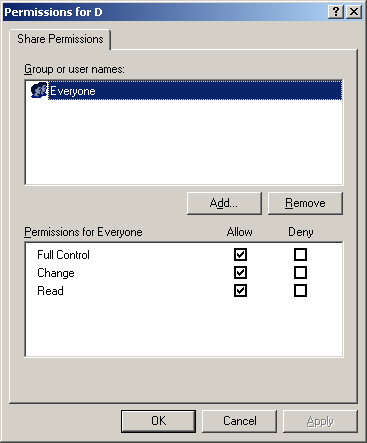

Share Permissions

Share permissions

constitute an access control mechanism that enables you to specify which

users and groups are permitted to access a shared resource over the

network, and what degree of access they should have. By default, when

the Windows Server 2003 operating system is installed, the Windows Setup

program creates only administrative shares. Each drive on the computer

has a hidden administrative share, named with the drive letter followed

by a dollar sign ($). These are special shares that you cannot delete,

and you cannot modify their permissions.

Tip

When

creating a file system share, appending a dollar sign to the share name

causes the Windows operating system to keep the share hidden. You

cannot see hidden shares when you browse the network using My Network

Places, but you can still access them by typing the share name in the

Run dialog box. For example, to access the administrative share on drive

C on a computer called Server01, you would type \\Server01\C$ in the Open text box in the Run dialog box. |

When

you create a new file system share on a computer running Windows Server

2003, by default the Everyone group receives only the Read permission.

You must modify the defaults to give users greater access to the share.

The Permissions dialog box you use to modify the share permissions is

shown in Figure 2.

This default is new to Windows Server 2003. On computers running the

Windows XP and Windows 2000 operating systems, the Everyone group

receives the Full Control permission on all newly created shares. You

must modify or remove this permission to control access to the shares.

Share

permissions are completely separate from file system permissions. File

system permissions affect all users, whether they are accessing the

drive over the network or sitting at the computer console. Share

permissions affect only users who are accessing the resource over the

network. A network user must therefore have both the appropriate file

system permissions and the appropriate share permissions to access a

shared drive or folder on a remote computer. Many

network administrators use either file system permissions or share

permissions to secure their drives, but not both, to avoid confusion.

Keep in mind, however, that securing a share does not prevent users from

accessing the share’s files from the computer’s console. For this

reason, it is common practice among many administrators to rely entirely

on file system permissions and not to use share permissions for access

control. |

|

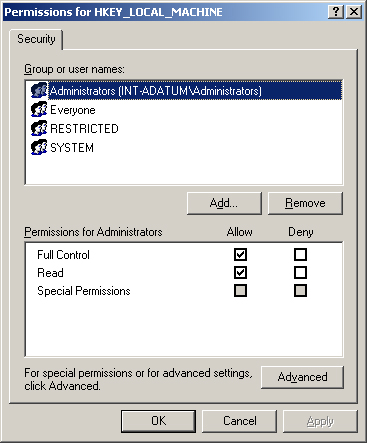

Registry Permissions

The

registry of the Windows operating system contains a great deal of

configuration data for many applications and many elements of the

operating system. Installing applications and configuring operating

system settings modifies registry elements. It is also possible to

modify the registry manually, but this is a dangerous practice because

even the slightest incorrect setting can cause a catastrophic

malfunction. To protect the registry, the Windows operating system

includes a separate system of permissions that enable you to specify who

has access to the registry and to what degree. You modify registry

permissions using the Registry Editor (Regedit.exe) program, using a

Permissions dialog box like the one shown in Figure 3.

By default,

members of the Administrators group have the Full Control permission for

all the keys in the registry. The Everyone group has the Read

permission only for the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE and HKEY_USERS keys, and the

Server Operators group has permissions that enable them to read, add,

and modify certain registry keys, without giving them full control. In

most cases, there is no need to modify registry permissions manually,

but if you want to create a class of administrative users that has

limited access, you might want to modify the permissions of the Server

Operators group.

Active Directory Permissions

Windows Server

2003 has yet another system of permissions, which you can use to specify

who can access and manage objects in the Active Directory database. On a

large network, working with Active Directory objects is a common

administrative task.

Administrators

frequently have to create or delete user objects or modify the

properties of existing objects. To delegate these tasks to other people,

you might want to modify the default permissions for all or part of the

Active Directory database.

When you create a new

Active Directory domain by assigning a computer running Windows Server

2003 the role of domain controller, the system creates default

permissions for the following groups:

Enterprise Admins Enterprise Admins is the only group that receives the Full Control permission over the entire domain.

Domain Admins and Administrators

The Domain Admins and Administrators groups both get a selection of

permissions that enable them to perform most Active Directory object

maintenance tasks. They can create objects and modify their properties,

for example, but they cannot delete objects.

Authenticated Users

The Authenticated Users group receives the Read permission for the

entire domain, plus a small selection of very specific Modify

permissions. For example, members of this group receive the Unexpire

Password permission, which enables them to change their own passwords

after an expiration period specified by an administrative policy.

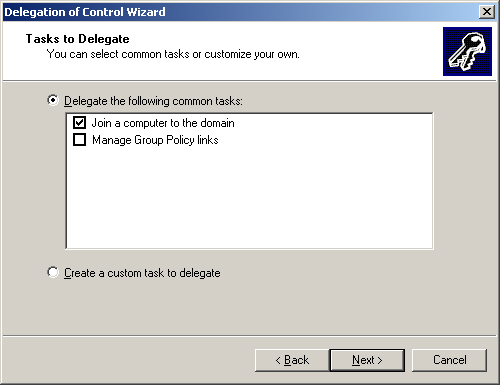

There are two ways to

modify the default permissions that the Windows operating system assigns

to Active Directory objects. You can use the Delegation Of Control

Wizard in the Active Directory maintenance snap-ins for the Microsoft

Management Console (MMC), or you can modify the permissions directly.

The Delegation Of Control Wizard simplifies the process of delegating

responsibility for a part of the Active Directory database to a user or

group (see Figure 4).

The

drawback of using the Delegation Of Control Wizard is that you cannot

view the permissions you have set once you have assigned them. To do

this, you must work with the permissions directly. By default, Windows

directory service tools such as Active Directory Users And Computers do

not provide direct access to the permissions. To modify this default,

you select the Advanced Features option from the console’s View menu.

Once you do this, the Properties dialog box for each Active Directory

object displays a standard Security tab, as shown in Figure 5.

Account Policy Settings

Group policies are among the most powerful security features included with Windows Server 2003. You can create Group Policy Objects (GPOs)

that do everything from distributing new software to configuring system

security settings to remapping directories. You then associate the

Group Policy Object with an Active Directory container object, such as a

domain, a site, or an organizational unit, and the Windows operating

system applies the policy to all the objects in that container.

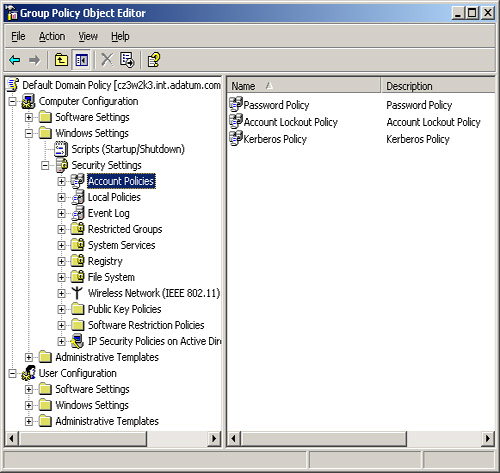

One of the security

modifications that Microsoft has made in Windows Server 2003 is to

enable some of the most commonly used policies by default. These are the

account policies, which you can find in the Computer

Configuration\Windows Settings\Security Settings heading in the Group

Policy Object Editor console (see Figure 6).

In

previous versions of the Windows operating system, these policies are

undefined by default. However, Windows Server 2003 enables the following

account policies by default and applies them to each domain:

Enforce Password History

Specifies the number of unique passwords that users have to supply

before the Windows operating system permits them to reuse an old

password. The default value is 24.

Maximum Password Age

Specifies how long a single password can be used before the Windows

operating system forces the user to change it. The default value is 42

days.

Minimum Password Age

Specifies how long a single password must be used before the Windows

operating system permits the user to change it. The default value is one

day.

Minimum Password Length

Specifies the minimum number of characters the Windows operating system

permits in user-supplied passwords. The default value is seven.

Password Must Meet Complexity Requirements

Specifies criteria for passwords, such as length of at least six

characters; no duplication of all or part of the user’s account name;

and inclusion of characters from at least three of the following four

categories: uppercase letters, lowercase letters, numbers, and symbols.

By default, the Windows operating system enables this policy.

Store Passwords Using Reversible Encryption

Specifies whether the Windows operating system should store user

passwords in an encrypted form that specific applications or protocols

can decrypt as needed. This policy weakens the security of the

authentication system; you should not enable it unless you are forced to

use an application or protocol that requires it. By default, this

policy is disabled.

Account Lockout Threshold Specifies

the number of failed logon attempts that causes the Windows operating

system to lock out users from future attempts until an administrator

resets the account. The default value is zero, which means that users

are allowed unlimited failed logon attempts.

Enforce User Logon Restrictions

Specifies whether the Kerberos Key Distribution Center (KDC) should

validate every request for a session ticket against the user rights

policy of the requesting user’s account. By default, this policy is

enabled.

Maximum Lifetime For Service Ticket

Specifies the amount of time that clients can use a Kerberos session

ticket to access a particular service. The default value is 600 minutes.

Maximum Lifetime For User Ticket

Specifies the maximum amount of time that users can utilize a Kerberos

ticket-granting ticket (TGT) before requesting a new one. The default

value is ten hours.

Maximum Lifetime For User Ticket Renewal Specifies the amount of time during which users can renew a Kerberos TGT. The default value is seven days.

Maximum Tolerance For Computer Clock Synchronization

Specifies the maximum time difference that Kerberos allows between the

client computer and the authentication server. The default value is five

minutes.

Tip

Windows

account policies have three possible states: enabled, disabled, and

undefined. The difference between disabled and undefined comes into play

when multiple Group Policy Objects apply to the same objects and the

Windows operating system must resolve policy conflicts. An enabled

policy always overrides an undefined instance of the same policy, but a

policy that is explicitly disabled might override an enabled instance of

the same policy. |

This default

configuration forces users to change their passwords every six weeks,

and compels them to use passwords that are not easy to guess. Policies

like Minimum Password Age and Enforce Password History prevent the users

from working around the password requirements by reusing the same few

passwords and repeatedly changing passwords over a short time. If you

want to increase the password security on your network, you can modify

these defaults by requiring longer passwords and more frequent changes.

You can also relax security by disabling some or all of these policies.

Tip

Be sure to understand the functions of the security configuration parameters in a Group Policy Object. |

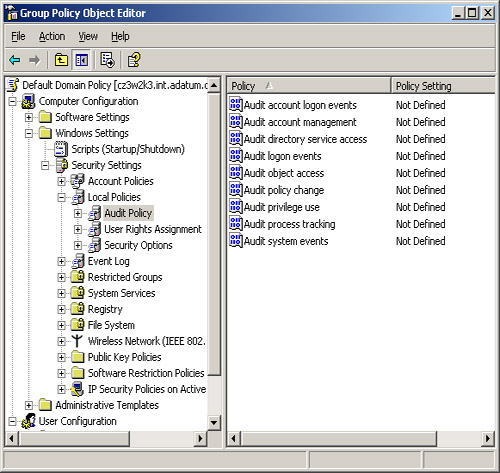

Audit Policies

Group

Policy Objects can contain audit policies specifying the activities

that the system should record in a log. You find the audit policies in

the Computer Configuration/ Windows Settings/Security Settings/Local

Policies header in the Group Policy Object Editor console (see Figure 7).

By default, domain objects do not have any audit policies defined, but

the GPO for the Domain Controllers organizational unit in each domain

does have audit policies.

By default, Windows Server 2003 enables the following audit policies for the Domain Controllers organizational unit:

For each of these

policies the default setting is to record only successful events in the

log. For example, with these settings, the system logs all successful

logons, but not the logon failures. If you are concerned about people

trying to penetrate account passwords using the brute force method

(trial and error), you might want to audit unsuccessful logon attempts

as well.

Tip

To

prevent brute force attacks, in addition to auditing unsuccessful

logons, you should consider modifying the default value of the Account

Lockout Threshold policy. This policy limits the number of unsuccessful

logon attempts by locking the account for a specified period or until an

administrator releases it. |