If the StackPanel has more elements than can be displayed on the screen (or in whatever container the StackPanel happens to find itself), the elements towards the bottom (or right) won’t be displayed.

If you fear that the phone’s screen is not large enough to fit all the children of your StackPanel, you can put the StackPanel in a ScrollViewer, a control that determines how large its content needs to be, and provides a scrollbar or two.

Actually, on Windows Phone 7, the scrollbars are more virtual than real. You don’t actually scroll the ScrollViewer with the scrollbars. You use your fingers instead. Still, it’s convenient to refer to scrollbars, so I will continue to do so.

By default, the vertical scrollbar is visible and the horizontal scrollbar is hidden, but you can change that with the VerticalScrollBarVisibility and HorizontalScrollBarVisibility properties. The options are members of the ScrollBarVisibility enumeration: Visible, Hidden, Auto (visible only if needed), and Disabled (visible but not responsive).

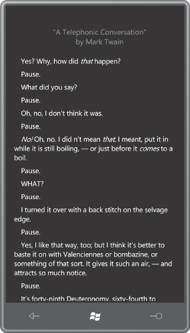

The next program is an ebook reader. Well, not exactly an ebook reader. It’s more like an eshort

reader, and I guess it’s not very versatile: It displays a little humor

piece written by Mark Twain in 1880 and believed to be the first

description of the experience of listening to a person talk on the

telephone without hearing the other side of the conversation. (The woman

talking on the telephone is Mark Twain’s wife, Olivia.)

I enhanced the customary application title a little bit to put it in a different color and make it two lines:

Example 1. Silverlight Project: TelephonicConversation File: MainPage.xaml (excerpt)

<StackPanel x:Name="TitlePanel" Grid.Row="0" Margin="24,24,0,12">

<TextBlock x:Name="ApplicationTitle"

Style="{StaticResource PhoneTextNormalStyle}"

TextAlignment="Center"

Foreground="{StaticResource PhoneAccentBrush}">

"A Telephonic Conversation"<LineBreak />by Mark Twain

</TextBlock>

</StackPanel>

|

The content grid includes its own Resources collection with a Style defined. The Grid contains a ScrollViewer, which contains a StackPanel, which contains all the TextBlock elements of the story, one for each paragraph. Notice the strict division of labor: The TextBlock elements display the text; the StackPanel provides the stacking; the ScrollViewer provides the scrolling:

Example 2. Silverlight Project: TelephonicConversation File: MainPage.xaml (excerpt)

<Grid x:Name="ContentPanel" Grid.Row="1" Margin="12,0,12,0">

<Grid.Resources>

<Style x:Key="paragraphStyle"

TargetType="TextBlock">

<Setter Property="TextWrapping" Value="Wrap" />

<Setter Property="Margin" Value="5" />

<Setter Property="FontSize" Value="{StaticResource PhoneFontSizeSmall}" />

</Style>

</Grid.Resources>

<ScrollViewer Padding="5">

<StackPanel>

<TextBlock Style="{StaticResource paragraphStyle}">

I consider that a conversation by telephone - when you are

simply sitting by and not taking any part in that conversation -

is one of the solemnest curiosities of this modern life.

Yesterday I was writing a deep article on a sublime philosophical

subject while such a conversation was going on in the

room. I notice that one can always write best when somebody

is talking through a telephone close by. Well, the thing began

in this way. A member of our household came in and asked

me to have our house put into communication with Mr. Bagley's,

down town. I have observed, in many cities, that the sex

always shrink from calling up the central office themselves. I

don't know why, but they do. So I touched the bell, and this

talk ensued: -

</TextBlock>

<TextBlock Style="{StaticResource paragraphStyle}">

<Run FontStyle="Italic">Central Office.</Run>

[Gruffly.] Hello!

</TextBlock>

<TextBlock Style="{StaticResource paragraphStyle}">

<Run FontStyle="Italic">I.</Run> Is it the Central Office?

</TextBlock>

. . .

<TextBlock Style="{StaticResource paragraphStyle}"

TextAlignment="Right">

- <Run FontStyle="Italic">Atlantic Monthly</Run>, June 1880

</TextBlock>

</StackPanel>

</ScrollViewer>

</Grid>

|

This is not the whole file, of course. The bulk of the story has been replaced by an ellipsis (…).

ScrollViewer is given a Padding value of 5 pixels so the StackPanel doesn’t go quite to the edges; in addition, each TextBlock gets a Margin property of 5 pixels through the Style. The result of padding and margin contributes to a composite space on both the left and right sides of 10 pixels, and 10 pixels also separate each TextBlock, making them look more like distinct paragraphs and aiding readability

I also put a Unicode

character   at the beginning of each paragraph. This is the

Unicode em-space and effectively indents the first line by about a

character width.

By default, ScrollViewer provides vertical scrolling. The control responds to touch, so you can easily scroll through and read the whole story.

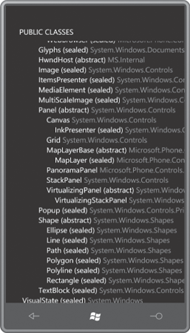

The PublicClasses program coming up next also has a ScrollViewer containing a vertical StackPanel, but it fills up that StackPanel entirely in code. Using

reflection, the code-behind file obtains all the public classes exposed

by the System.Windows, Microsoft.Phone, Microsoft.Phone.Controls, and

Microsoft.Phone.Controls.Maps assemblies, and lists them in a class

hierarchy.

In preparation for this job, the XAML file contains an empty StackPanel identified by name:

Example 3. Silverlight Project: PublicClasses File: MainPage.xaml (excerpt)

<Grid x:Name="ContentPanel" Grid.Row="1" Margin="12,0,12,0">

<ScrollViewer HorizontalScrollBarVisibility="Auto">

<StackPanel Name="stackPanel" />

</ScrollViewer>

</Grid>

|

By default, the VerticalScrollBarVisibility is Visible, but I’ve given the HorizontalScrollBarVisibility property a value of Auto. If any line of text in the StackPanel is too long to be displayed on the screen, horizontal scrolling will be allowed to bring it into view.

This horizontal scrolling represents a significant difference between this program and the previous one. You don’t want horizontal

scrolling when text is wrapped into paragraphs as it is in the

TelephonicConversation project. But in this program, non-wrapped lines

are displayed that might be wider than the width of the display, so

horizontal scrollbar is desirable.

The code-behind file makes use of a separate little class named ClassAndChildren to store the tree-structured classes:

Example 4. Silverlight Project: PublicClasses File: ClassAndChildren.cs

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

namespace PublicClasses

{

class ClassAndChildren

{

public ClassAndChildren(Type parent)

{

Type = parent;

SubClasses = new List<ClassAndChildren>();

}

public Type Type { set; get; }

public List<ClassAndChildren> SubClasses { set; get; }

}

}

|

The program creates a ClassAndChildren object for each class that is displayed in the tree, and each ClassAndChildren object contains a List object with all the classes that derive from that class.

Here’s the complete code portion of the MainPage class. It needs a using directive for System.Reflection.

Example 5. Silverlight Project: PublicClasses File: MainPage.xaml.cs (excerpt)

public partial class MainPage : PhoneApplicationPage

{

Brush accentBrush;

public MainPage()

{

InitializeComponent();

accentBrush = this.Resources["PhoneAccentBrush"] as Brush;

// Get all assemblies

List<Assembly> assemblies = new List<Assembly>();

assemblies.Add(Assembly.Load("System.Windows"));

assemblies.Add(Assembly.Load("Microsoft.Phone"));

assemblies.Add(Assembly.Load("Microsoft.Phone.Controls"));

assemblies.Add(Assembly.Load("Microsoft.Phone.Controls.Maps"));

// Set root object (use DependencyObject for shorter list)

Type typeRoot = typeof(object);

// Assemble total list of public classes

List<Type> classes = new List<Type>();

classes.Add(typeRoot);

foreach (Assembly assembly in assemblies)

foreach (Type type in assembly.GetTypes())

if (type.IsPublic && type.IsSubclassOf(typeRoot))

classes.Add(type);

// Sort those classes

classes.Sort(TypeCompare);

// Now put all those sorted classes into a tree structure

ClassAndChildren rootClass = new ClassAndChildren(typeRoot);

AddToTree(rootClass, classes);

// Display the tree

Display(rootClass, 0);

}

int TypeCompare(Type t1, Type t2)

{

return String.Compare(t1.Name, t2.Name);

}

// Recursive method

void AddToTree(ClassAndChildren parentClass, List<Type> classes)

{

foreach (Type type in classes)

{

if (type.BaseType == parentClass.Type)

{

ClassAndChildren subClass = new ClassAndChildren(type);

parentClass.SubClasses.Add(subClass);

AddToTree(subClass, classes);

}

}

}

// Recursive method

void Display(ClassAndChildren parentClass, int indent)

{

string str1 = String.Format("{0}{1}{2}{3}",

new string(' ', indent * 4),

parentClass.Type.Name,

parentClass.Type.IsAbstract ? " (abstract)" : "",

parentClass.Type.IsSealed ? " (sealed)" : "");

string str2 = " " + parentClass.Type.Namespace;

TextBlock txtblk = new TextBlock();

txtblk.Inlines.Add(str1);

txtblk.Inlines.Add(new Run

{

Text = str2,

Foreground = accentBrush

});

stackPanel.Children.Add(txtblk);

foreach (ClassAndChildren child in parentClass.SubClasses)

Display(child, indent + 1);

}

}

|

The constructor starts out

storing all the public classes from the major Silverlight assemblies in

a big collection. These are then sorted by name, and apportioned into ClassAndChildren objects in a recursive method. A second recursive method adds TextBlock elements to the StackPanel. Notice that each TextBlock element has an Inlines collection with two Run objects. An earlier version of the program

wasn’t very easy to read, so I decided the namespace name should be in a

different color, and for convenience I used the accent color chosen by

the user.

Here’s the portion of the class hierarchy showing Panel and its derivatives: