In the “old days,” working on a document usually

meant pulling out a blank sheet of paper, taking up a pen (or some other

writing instrument), and then writing out your thoughts in longhand.

Nowadays, of course, electronic document editing supersedes this

pen-and-paper approach almost entirely. However, there are still plenty

of situations when people still write things out in longhand:

Jotting down an address or other data while on the phone

Taking notes at a meeting

Recording a list of things to do while visiting a client

Creating a quick map or message for faxing

Sketching out ideas or blueprints in a brainstorming session

Unfortunately, for all but

the most trivial notes, writing on paper is inefficient because you

eventually have to put the writing into electronic form, either by

entering the text by hand or by scanning the document.

What the world has needed

for a long time is a way to bridge the gap between purely digital and

purely analog writing. We’ve needed a way to combine the convenience of

the electronic format with the simplicity of pen-based writing. After

several aborted attempts (think of the Apple Newton), that bridge was

built in recent years: the Tablet PC. At first glance, many Tablet PCs

look just like small notebook computers, and they certainly can be used just like any notebook. However, a Tablet PC boasts three hardware innovations that make it unique:

A touch screen

(usually pressure-sensitive) that replaces the usual notebook LCD

screen. Some Tablet PC screens respond to touch, but most respond to

only a specific type of pen (discussed next).

A digital pen

or stylus that acts as an all-purpose input device: You can use the pen

to click, double-click, click-and-drag, and tap out individual

characters using an onscreen keyboard. In certain applications, you can

also use the pen to “write” directly on the screen, just as though it

were a piece of paper, thus enabling you to jot notes, sketch diagrams,

add proofreader marks, or just doodle your way through a boring meeting.

The

ability to reorient the screen physically so that it lies flat on top

of the keyboard, thus making the screen’s orientation like a tablet or

pad of paper. (Note, however, that there are now some Tablet PCs that

don’t support this feature and have lids like regular notebooks.)

Note

Some Tablet PCs come with a screen that’s sensitive to finger touches. Windows Vista supports these screens.

The first Tablet PCs came

with their own unique operating system: Windows XP Tablet PC Edition.

With Windows Vista, the Tablet PC–specific features are now built into

the regular operating system, although they are activated only when

Vista is installed on a Tablet PC (and you’re running any Vista edition

except Home Basic).

Before moving on to the new

Tablet PC, I should note that Vista comes with a couple of tools that

were also part of the XP version: Windows Journal and Sticky Notes.

These programs are identical to the XP versions.

Changing the Screen Orientation

The first Tablet PC feature to mention is one that you’ve already seen.

The new Mobility Center comes with a Screen Orientation section that

tells you the current screen orientation . There are four settings in all:

Primary Landscape—

This is the default orientation, with the taskbar at the bottom of the

display and the top edge of the desktop at the top of the display.

Secondary Portrait—

This orientation places the taskbar at the right edge of the display,

and the top edge of the desktop at the left of the display.

Secondary Landscape— This orientation places the taskbar at the top of the display, and the top edge of the desktop at the bottom of the display.

Primary Portrait— This

orientation places the taskbar at the left edge of the display, and the

top edge of the desktop at the right of the display.

Setting Tablet PC Options

Before you start

inking with Vista, you’ll probably want to configure a few settings, and

Vista offers quite a few more than XP. Your starting point is the

Control Panel’s Mobile PC window—specifically, the renamed Tablet PC

Settings icon (formerly named Tablet and Pen Settings). Select Start, Control Panel, Mobile PC, Tablet PC Settings.

In the Tablet PC

Settings dialog box that appears, the General tab is basically the same

as the old Settings tab (you can switch between right-handed or

left-handed menus and calibrate the pen), and the Display tab is

identical to its predecessor (it offers another method to change the

screen orientation).

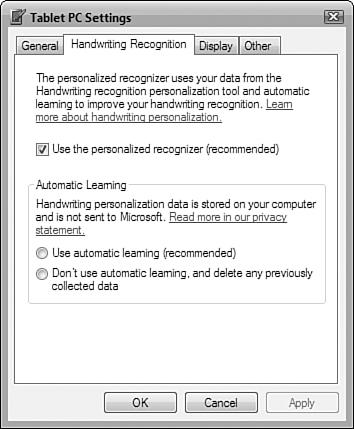

However, the new Handwriting Recognition tab has two sections (as shown in Figure 1):

Personalization— This increases the accuracy of the handwriting recognizer

(the feature that converts handwritten text into typed text), but only

when the Use the Personalized Recognizer check box is activated.

Automatic Learning—

This feature collects information about your writing, including the

words you write and the style in which you write them. Note that this

applies not only to your handwriting—the ink you write in the Input

Panel, the recognized text, and the corrected text—but also to your

typing, including email messages and web addresses typed into Internet

Explorer. To use this feature, activate the Use Automatic Learning

option.

Working with the Tablet PC Input Panel

As with XP Tablet PC

Edition, Windows Vista comes with the Tablet PC Input Panel tool that

you use to enter text and other symbols with the digital pen instead of

the keyboard. You have two ways to display the Input Panel:

In Vista, an icon

for the Input Panel appears in a small tab docked on the left edge of

the screen. Hover the mouse pointer over the tab to display it, and then

click the icon or any part of the tab.

Move

the pen over any area in which you can enter text (such as a text box).

In most cases, the Input Panel icon appears near the text entry area.

Click the icon when it appears.

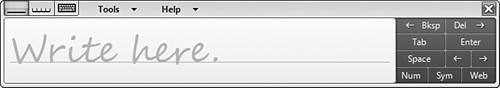

Figure 2 shows the Input Panel.

Tip

You can also add an icon

for the Input Panel to the Vista taskbar. Right-click the taskbar and

then click Toolbars, Tablet PC Input Panel.

The

layout of the Input Panel is slightly different from the XP version,

with the icons for the writing pad, character pad, and onscreen

Keyboard, and the Options button along the top. The miniature keyboard

that appears with the writing pad and character pad is slightly

different as well, with the notable difference being the addition of the

Web key full time. (In XP Tablet PC Edition, the Web key appeared only

when you were entering a web address.) This makes sense because users

often need to write URLs in email messages and other correspondence.

The Vista Input Panel also comes with quite a few more options than its predecessor. Vista gives you two ways to see them:

In the Input Panel, click Tools and then click Options in the menu that appears.

In the Tablet PC Settings dialog box, display the Other tab and click the Go to Input Panel Settings link.

Here’s a list of some of the more significant new settings:

AutoComplete

(Settings tab)— When this check box is activated, the Input Panel

automatically completes your handwriting if it recognizes the first few

characters. For example, if you’re writing an email address that you’ve

entered (via handwriting or typing) in the past, Input Panel recognizes

it after a character or two and displays a banner with the completed

entry. You need only click the completed entry to insert it. This also

works with web addresses and filenames.

Show the Input Panel Tab

(Opening tab)— Use this check box to toggle the Input Panel tab on and

off. For example, if you display the Tablet PC Input Panel toolbar in

the taskbar, you might prefer to turn off the Input Panel tab.

You Can Choose Where the Input Panel Tab Appears (Opening tab)— Choose either On the Left Edge of the Screen (the default) or On the Right Edge of the Screen.

New Writing Line

(Writing Pad tab)— Use this slider to specify how close to the end of

the writing line you want to write to before starting a new line

automatically.

Gestures

(Gestures tab)— In XP Tablet PC Edition, you could delete handwritten

text by “scratching it out” using a Z-shape gesture. Many people found

this hard to master and a bit unnatural, so Vista offers several new

scratch-out gestures, which you turn on by activating the All

Scratch-Out and Strikethrough Gestures option.

Note

Vista offers four new scratch-out gestures:

Strikethrough— A horizontal line (straight or wavy) through the text.

Vertical scratch-out— An M- or W-shaped gesture through the text.

Circular scratch-out— A circle or oval around the text.

Angled scratch-out—

An angled line (straight or wavy) through the text. The angle can be

from top left to bottom right, or from bottom left to top right.

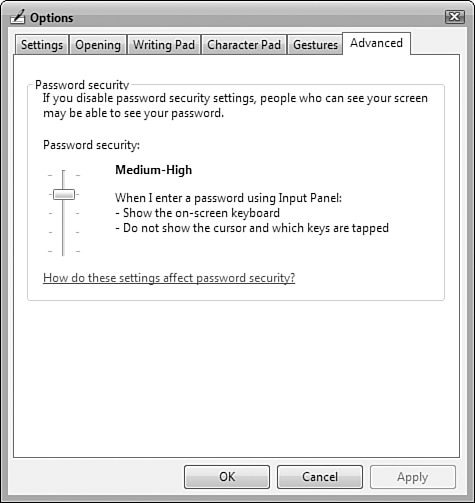

Password Security (Advanced tab)— This slider (see Figure 3)

controls the security features that Vista uses when you use the pen to

enter a password into a password text box. At the High setting, Vista

automatically switches to the onscreen keyboard (and doesn’t allow you

to switch to the writing pad or character pad) and doesn’t show the pen

pointer or highlight the keys that you tap while entering the password.

Using Pen Flicks

The Input Panel onscreen keyboard has keys that you can tap with your

pen to navigate a document and enter program shortcut keys. However, if

you just want to scroll through a document or navigate web pages, having

the keyboard onscreen is a hassle because it takes up so much room. An

alternative is to tap-and-drag the vertical or horizontal scroll box, or

tap the program’s built-in navigation features (such as the Back and

Forward buttons in Internet Explorer).

Vista gives you a third choice for navigating a document: pen flicks.

Pen flicks are gestures that you can use in any application to scroll

up and down in a document, or to navigate backward or forward in

Internet Explorer or Windows Explorer:

Scroll up (about one screenful)— Move the pen up in a straight line

Scroll down (about one screenful)— Move the pen down in a straight line

Navigate back— Move the pen to the left in a straight line

Navigate forward— Move the pen right in a straight line

Tip

For a pen flick to work, you need to follow these techniques:

Move the pen across the screen for about half an inch (at least 10mm)

Move the pen very quickly

Move the pen in a straight line

Lift your pen off the screen quickly at the end of the flick

You can also set up pen flicks for other program features:

Copy— Move the pen up and to the left in a straight line

Paste— Move the pen up and to the right in a straight line

Delete— Move the pen down and to the right in a straight line

Undo— Move the pen down and to the left in a straight line

To activate and configure flicks, follow these steps:

1. | Select Start, Control Panel, Mobile PC, Pen and Input Devices. The Pen and Input Devices dialog box appears.

|

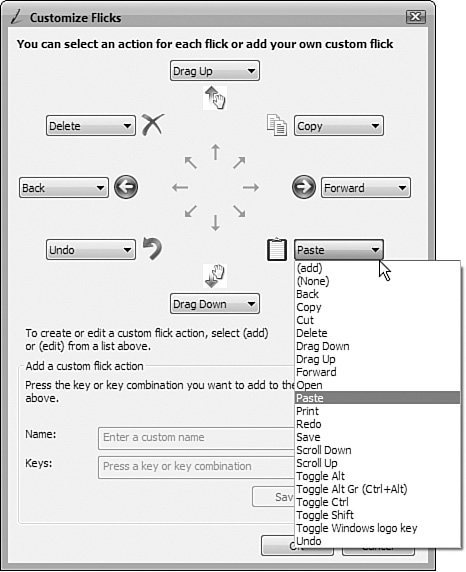

2. | Display the Flicks tab, shown in Figure 4.

|

3. | Activate the Use Flicks to Perform Common Actions Quickly and Easily check box.

|

4. | Select the flicks you want to use:

- Navigational Flicks— Activate this option to use the Scroll Up, Scroll Down, Back, and Forward flicks.

- Navigational Flicks and Editing Flicks— Activate this option to also use the Copy, Paste, Delete, and Undo flicks in any program.

|

If you activate the

Navigational Flicks and Editing Flicks option, the Customize button

enables. Click this button to display the Customize Flicks dialog box

shown in Figure 5.

You use this dialog box to apply one of Vista’s built-in actions (such

as Cut, Open, Print, or Redo) to a flick. Alternatively, click (add) to

create a custom action by specifying a key or key combination to apply

to the flick.

Tip

If you forget which flick

performs which action, you can easily find out by displaying the Pen

Flicks icon in the taskbar’s notification area. In the Flicks tab,

activate the Display Flicks Icon in the Notification Area check box.

(Note that the icon doesn’t show up until you attempt at least one

flick.) Clicking this icon displays the Current Pen Flicks Settings

fly-out that shows your current flick setup.

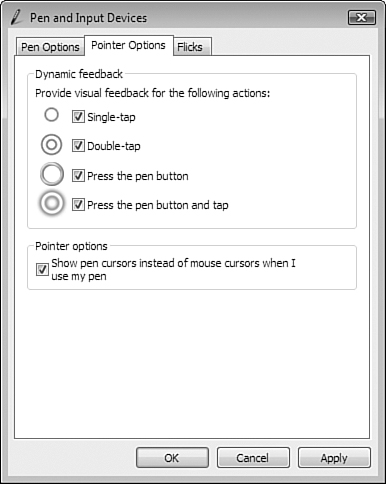

Setting Pointer Options

While we’re in the Pen and Input Devices dialog box, I should also point out the new Pointer Options tab, shown in Figure 6.

By default, Vista provides you with visual feedback when you single-tap

and double-tap the pen and when you press the pen button. I find that

this visual feedback helps when I’m using the pen for mouse-like

actions. If you don’t, you can turn them off by deactivating the check

boxes.

Personalizing Handwriting Recognition

When you use a Tablet PC’s digital pen as an input device, there will

often be times when you don’t want to convert the writing into typed

text. A quick sticky note or journal item might be all you need for a

given situation. However, in plenty of situations, you need your

handwriting converted into typed text. Certainly, when you’re using the

Input Panel, you always want the handwriting converted to text. However,

the convenience and usefulness of handwritten text directly relates to

how well the handwriting recognizer does its job. If it misinterprets

too many characters, you’ll spend too much time either correcting the

errors or scratching out chunks of text and starting again.

Rather than just throwing

up their hands and saying “That’s life with a Tablet PC,” Microsoft’s

developers are doing something to ensure that you get the most out of

the handwriting recognizer. Windows Vista comes with a new tool called

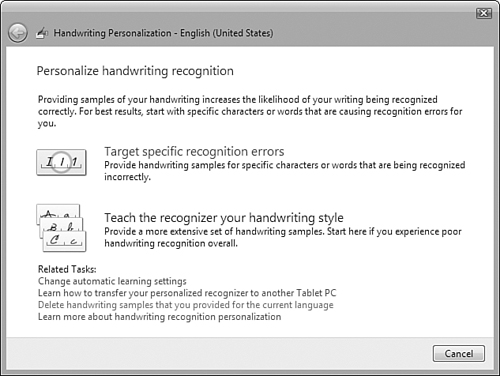

Handwriting Personalization (select Start, All Programs, Tablet PC,

Personalize Handwriting Recognition), shown in Figure 7.

This feature gives

you two methods that improve the Tablet PC’s capability to recognize

your handwriting (you can run separate recognition chores for each user

on the computer):

Target Specific Recognition Errors—

With this method you teach the handwriting recognizer to handle

specific recognition errors. This is the method to use if you find that

the Tablet PC does a pretty good job of recognizing your handwriting,

but often incorrectly recognizes certain characters or words. By

providing handwritten samples of those characters or words and

specifying the correct conversion for them, you teach the handwriting

recognizer to avoid those errors in the future.

Teach the Recognizer Your Handwriting Style—

With this method, you teach the handwriting recognizer to handle your

personal style of handwriting. This is the method to use if you find

that the Tablet PC does a poor job of recognizing your handwriting in

general. In this case, you provide a more comprehensive set of

handwritten samples to give the handwriting recognizer an overall

picture of your writing style.

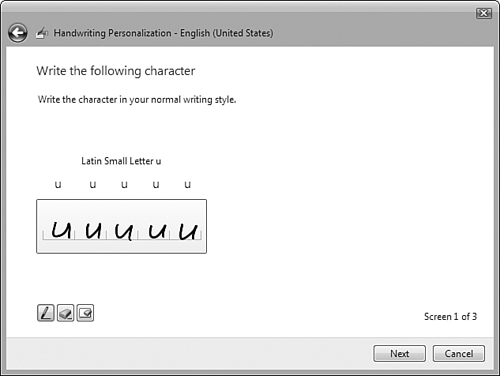

If you select Target Specific Recognition Errors, you next get a choice of two wizards:

Character or Word You Specify—

Run this wizard if a character or word is consistently being recognized

incorrectly. For a character, you type the character and then provide

several samples of the character in handwritten form, as shown in Figure 8 (for the lowercase letter u,

in this case). The wizard then asks you to provide handwritten samples

for a few characters that are similarly shaped. Finally, the wizard asks

for handwritten samples of words that contain the character. For a

word, the wizard asks you to type the word; then it asks you to write

two samples of the word by hand.

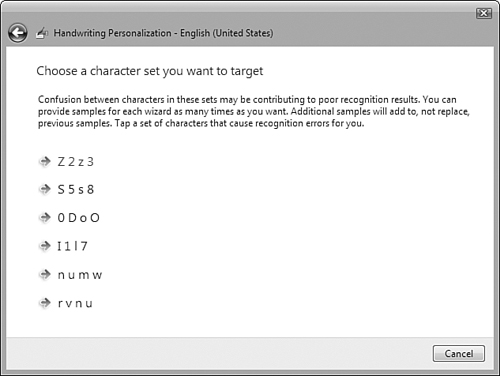

Characters with Similar Shapes—

Run this wizard if a particular group of similarly shaped characters is

causing you trouble. The wizard gives you a list of the six sets of

characters that most commonly cause recognition problems, as shown in Figure 9.

After you choose a set, the wizard goes through each character and asks

you to write by hand several samples of the character and of the

character in context.

If you select Teach the Recognizer Your Handwriting Style, you get a choice of two wizards:

Sentences—

This wizard displays a series of sentences, and you provide a

handwritten sample for each. Note that there are 50 (!) sentences in

all, so wait until you have a lot of spare time before using this

wizard. (The wizard does come with a Save for Later button that you can

click at any time to stop the wizard and still preserve your work. When

you select Sentences again, the program takes you automatically to the

next sentence in the sequence.)

Numbers, Symbols, and Letters— This wizard consists of eight screens that take you through the numbers 0 to 9; common symbols such as !, ?, @, $, &, +, #, <, and >; and all the uppercase and lowercase letters. You provide a handwritten sample for each number, symbol, and letter.

When you’re done, click

Update and Exit to apply your handwriting samples to the recognizer.

Note that this takes a few minutes, depending on the number of samples

you provided.

Using the Snipping Tool

Windows Vista includes a feature called the Snipping Tool

that enables you to use your pen to capture (“snip”) part of the screen

and save it as an image or HTML file. Here’s how it works:

1. | Select

Start, All Programs, Accessories, Snipping Tool. When you first launch

the program, it asks if you want the Snipping Tool on the Quick Launch

toolbar.

|

2. | Click

Yes or No, as you prefer. Vista washes out the screen to indicate that

you’re in snipping mode and displays the Snipping Tool window.

|

3. | Pull down the New list and select one of the following snip types:

- Free-Form Snip— Choose this type to draw a freehand line around the screen area you want to capture

- Rectangular Snip— Choose this type to draw a rectangular line around the screen area you want to capture

- Window Snip— Choose this type to capture an entire window by tapping it

- Full-Screen Snip— Choose this type to capture the entire screen by tapping anywhere on the screen

|

4. | Use

your pen to define the snip, according to the snip type you chose. The

snipped area then appears in the Snipping Tool window, as shown in Figure 10. From here, you save the snip as an HTML file or a GIF, JPEG, or PNG graphics file.

|