Domains are more fun than forests because a lot of the

real administrative work goes on at this level. It's where you place

most of your users, groups, and resources. It's where you assign most

group policies, and most of the time it's where the servers that run all

your services are. Plus, there's something really neat about browsing

through Active Directory and finding the machine that's running your web

box, then finding the machine that contains your DNS, and knowing full

well that you can make almost anything you want happen (well, anything

within the security policy, that is). You don't want to start deleting

or bringing down your servers. That wouldn't be pleasant at all.

1. Domain Functional Levels

For each domain—just as for

each forest—you have to make a decision: at which functional level does

the domain need to operate? Normally, this is based on the type of

servers you have and the operations that are being conducted. But

remember, a domain's functional level is limited by the forest's

operating level. It's easy to go up, but not easy to go down.

Just like the Active

Directory forest operating level, each domain functional level has its

own advantages and limitations, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Functional Level Advantages and Limitations

| Domain Functional Level | Available Features | Supported Domain Controllers |

|---|

| Windows 2000 Native | Universal groups Group nesting Group conversion SIDs—security identifiers | Windows 2000 Server Windows Server 2003 Windows Server 2008 |

| Windows Server 2003 | Netdom.exe Logon timestamp updates Set userPassword as the effective password on inetOrgPerson and user objects

Ability to redirect User and Computer containers Authorization Manager can store authentication policies in AD DS

Constrained delegation Selective authentication | Windows Server 2003

Windows Server 2008 |

| Windows Server 2008 | Distributed File System (DFS) AES encryption supported for Kerberos Last interactive logon information Fine-grained password policies | Windows Server 2008 |

|

2. Single and Multiple Domains

A single-domain

architecture is a design where within a forest there is only one single

domain, usually functioning as a domain controller. At this level, most

domain administrators are also enterprise administrators. It's rare to

see a situation in which a large organization has only one domain with

no subdomains or other administrative breakdowns.

The advantage to having a

single domain is simplicity. If you have everything in one spot, it's

difficult to get lost in the maze of administrative breakdowns, the

schema will not be complex, and Group Policy has less of a chance (but

still a significant one) of running amok.

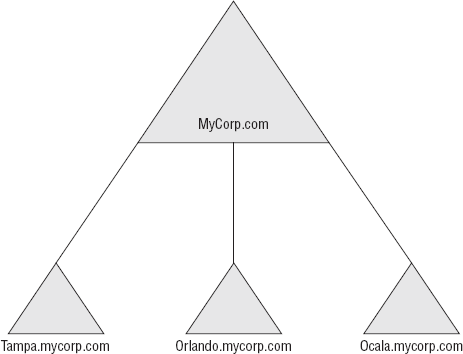

A much more realistic design structure (one much more often seen both in the real world and on the exam) is a multiple-domain

architecture wherein an organization has multiple websites, locations,

departments, or other signifying differentiations that require the

administrative structure to be broken down into simpler parts. See Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively, for illustrations of a simple-domain architecture and a multiple-domain architecture.

On the certification exam,

it's much more likely you will come across a more specific domain model

structure, such as a regional, x, or y model.

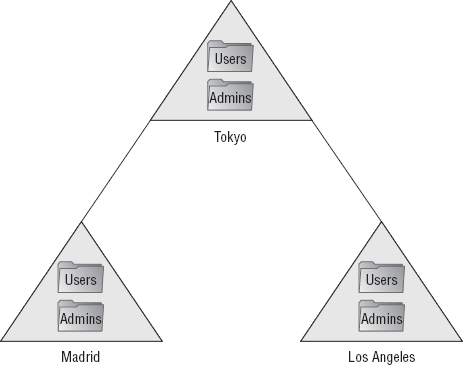

3. Regional Domain Model

In most international and

large-scale companies, users are often divided into several geographic

locations, such as Tokyo, Madrid, Hong Kong, and Los Angeles.

Historically, the only way to connect these locations has been via a

wide area network (WAN) connection over a relatively slow bandwidth

link.

In a regional design, each of

these regions is assigned their own specific domain where they can be

further subdivided into more closely knit administrative groups. Figure 3 shows an example of this type of domain structure.

Sometimes when you need to

isolate particular services using an autonomous model (not an isolation

model!), it becomes necessary for you to create a multiple tree

infrastructure wherein services or data are allocated among separate

domain trees in a fashion that allows for a broader form of

administration. You can see this model in action in Figure 4.

The main advantage of this

model is that you manage to achieve a form of autonomous separation, but

you also get to maintain the simplicity of a single schema. And if

there's one aspect of Windows Server that's annoying to mess with, it's

the schema.

Of course, this structure

has drawbacks. Specifically, if you decide to use this form of

administration, you remove the option to have complete isolation.

Because the domain trees all are in the same forest, the root-level

domain will have access to the rest of the trees and therefore will be

able alter important information—something that you, as an enterprise

administrator, may not want to have happen. Additionally, authentication

paths usually take longer in this model because users have to cross

separate servers to authenticate across links that are farther away.

4. Creating Your Domain Structure

Now that you've seen

the elements required to create an effective domain infrastructure, I'll

discuss how to put them together effectively.

The process for this,

once you understand the elements involved, is rather simple. Here are

the steps for domain structure creation:

Determine the administrative model.

Centralized

Decentralized

Hybrid

Choose the number of domains.

Assign your domain functional levels.

5. Active Directory Authentication

One of the most important tasks when creating your overall design (if you ask your security administrator, the

most important task) is to make sure the right people have access to

the right information at the right time. In the administrative world, we

call these processes authentication and authorization:

Authentication

In security administration,

authentication is the process of verifying a user's identity. Is John Q.

Smith really John Q. Smith? Or is he another user pretending to be John

Q. Smith?

Authorization

Authorization is the

process of determining what access a particular user has. For example,

this is the process of determining whether John Q. Smith has access to

the Shared folder on an office server located in the main building.