A basic understanding of how email works is critical

to managing an email system efficiently. Email is a client/server

application that enables a client to send messages to any other client

with only a simple identifying address. Between the sending and

receiving clients is a system of email servers that communicate with

each other using specialized protocols, such as the Simple Mail Transfer

Protocol (SMTP).

As with most networking subjects, email communication can be extremely

complicated, but the typical small business network administrator does

not need to delve into the technical details too deeply. The following

sections examine some of the most basic concepts, however, and describe

how they pertain to Windows SBS 2011.

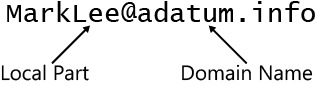

1. Understanding Email Addresses

As all email users know, an email address consists of a single user name, followed by an @ character and a domain name, as shown in Figure 1. The first part of the address, the part before the @ sign, is the local part, which needs to be understood only by the destination mail server. The part after the @ sign identifies the domain on the Internet where the destination client is located.

Routers on the Internet use

the network identifier to forward IP datagrams to a particular

destination network and then the router on the destination network uses

the host identifier to forward the datagrams to the correct computer on

that network. In the same way, the Domain Name System (DNS) identifies

computers using fully qualified domain names (FQDNs), which consist of

two parts: a host name and a domain name. When a DNS server tries to

resolve an FQDN into an IP address, it forwards the name resolution

request to the authoritative server for the domain, which looks up the

IP address of the specified host.

Email communications function in much the same way. The SMTP

servers on the Internet read only the second part of the email address

and forward the email message to the mail server for the appropriate

domain. Then, the domain mail server reads the first part of the

address—the part before the @ sign—and deposits the email message in the

mailbox for the appropriate user.

Because the domain name of an

email address must be understandable to all the servers on the Internet,

it must conform to the same standards as all DNS domain names.

Therefore, the domain name part of an email address is subject to the

following limitations:

The domain name can be no more than 255 characters long.

Domain names can consist only of the letters A to Z, the numbers 0 to 9, and the hyphen (-) character.

Domain names are not case-sensitive.

Because the local part of an

email address has to be read and understood only by the destination mail

server, its specifications are less stringent. The local part of an

email address is subject to the following limitations:

The local part of the name can be no more than 64 characters long.

Local part names can consist of the letters A to Z, the numbers 0 to 9, and the following characters: ! # $ % & ´ * + - / = ? ^ _ ` { | } ~.

Local

part names can also contain the period (.) character as long as it does

not appear as the first or last character and as long as it does not

appear twice in succession.

Local part names can conceivably be case-sensitive, but in Exchange Server 2010, they are not. Exchange Server delivers the addresses [email protected][email protected] to the same mailbox. and

Local part names can be

case-sensitive because their interpretation is left solely to the

destination email server. If a particular server implementation supports

case-sensitive local part names, and the destination server is running

that implementation, then the distinction of two local part names that

differ only in their case is possible. However, on the Internet, senders rarely know what server implementations their recipients are using, so most email

servers, including Exchange Server 2010, follow the recommendation of

the SMTP standard and treat all local part names as case-insensitive.

Windows SBS 2011 does not allow you to create two user accounts with email addresses that differ only in case.

Note:

Some email servers impose

other restrictions on local part name construction. For example, the

Windows Live Hotmail system limits local part names to letters; numbers;

and the period (.), hyphen (-), and underscore (_) characters. You

cannot create a Hotmail account name using any other characters, and the

Hotmail system does not send email to any address using other

characters.

Despite the limitations

listed earlier, one of your primary goals when assigning email addresses

should always be user-friendliness. An email address like hknjv!fgjyc8*pi09iponi0-v665q{[email protected]

would be technically legal, but it would be terribly inconvenient for

the individuals forced to use it or anyone trying to remember it.

2. Understanding Email Server Functions

Email clients have two

basic messaging functions: They send outgoing mail to one kind of server

and they retrieve incoming mail from another. The servers conduct the

rest of the email communication process, including the transmission of

messages to computers hundreds or thousands of miles away. The following

sections discuss the main email server types.

Note:

It is critical to realize that in this discussion of email communications, the term server

does not necessarily refer to a separate computer, but instead to a

process running on a computer in the form of an application or service. A

single computer can perform multiple server functions, as in the case

of a computer running Exchange Server 2010, which can perform all the

email server roles simultaneously.

2.1. Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP)

SMTP is the primary email communication protocol, responsible for the majority of email traffic on the Internet. Every email

client has the name or IP address of an SMTP server in its

configuration settings, to which it transmits its outgoing mail

messages. Email servers can use SMTP for both incoming and outgoing traffic.

SMTP is a text-based,

application layer protocol that email clients use to send their outgoing

messages to a server, and email servers use it to forward the messages

to other servers. Windows SBS 2011 servers function as SMTP

servers, as can all computers running Exchange Server 2010. Whichever

email client your users choose to run, that client sends its outgoing

email messages to the Windows SBS 2011 server using SMTP. If the

intended recipient of a message is another user on your network, the

Windows SBS server deposits the message in the recipient’s Exchange

mailbox. If the message is addressed to a user in another domain, the

server transmits the message to another SMTP server on the Internet.

An SMTP server is a

relatively simple mechanism, but its role has been complicated over the

years by the increasing prevalence on the Internet of unsolicited email

traffic, also known as spam.

In earlier days, Internet service providers (ISPs) set up SMTP servers

for their customers, connected them to the Internet, and left them open

for use by anyone. The well-known port number for the SMTP protocol is

25, and those servers willingly accepted anyone’s outgoing SMTP email

messages as long as they were addressed to that port.

However, it was not long before

spammers began using these open servers to send millions of unsolicited

messages. By using the SMTP servers belonging to other ISPs, the

spammers made it difficult, if not impossible, to trace their spam

emails back to them. As a result of the enormous amounts of bandwidth

consumed by the spam, ISPs were forced to add various forms of

protection to their SMTP servers.

Most Internet SMTP

servers today require users to authenticate before they can submit

outgoing traffic, and many of them refuse all traffic addressed to port

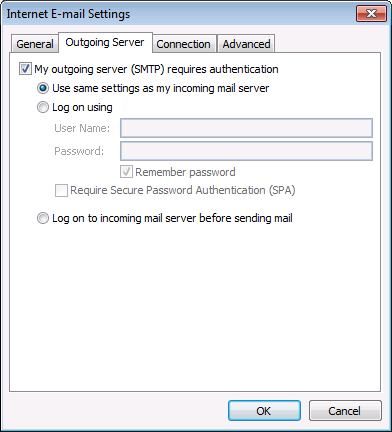

number 25. Email clients typically enable users to specify the

credentials they should use to log on to the SMTP server, as shown in Figure 2,

as well as an alternative to port number 25. Port number 587 has been

standardized as the port for authenticated outgoing mail submissions,

but some ISPs use nonstandard ports instead.

Note:

On a Windows SBS 2011 network, the computer functioning as the SMTP

server is not accessible directly from the Internet, so it is not

subject to abuse by spammers outside the local network. Therefore, it is

not necessary to take these protective measures.

2.2. Post Office Protocol Version 3 (POP3)

SMTP is strictly a “push” protocol. Email clients and other email

servers send messages to SMTP servers; they do not retrieve messages

from them. To retrieve their incoming messages from a server, clients

use one of two “pull” protocols: Post Office Protocol version 3 (POP3) or Internet Message Access Protocol version 4 (IMAP4). POP3 is the more popular of these protocols.

Note:

The standard for version 3

of POP was published in 1996. POP1 and POP2 have long since become

obsolete, and any reference to POP without a version identifier almost

certainly refers to POP version 3. There is a Post Office Protocol

version 4 (POP4) server in development, but the protocol has not yet

been standardized, nor is it commercially available.

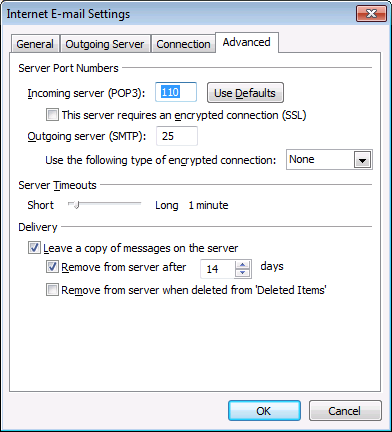

POP3 is a relatively simple protocol that is designed to provide clients with offline access to their email

messages. A POP3 server maintains a separate mailbox for each user in a

particular domain, whereas the server stores the incoming email

messages it receives through its SMTP connections. Email clients

periodically connect to the server, authenticate the user, and download

the messages in the user’s mailbox. In most cases, the server deletes

the messages once the client has downloaded them, but many POP3

implementations provide users with the ability to leave copies of the

downloaded messages on the server, as shown in Figure 3.

The design of the

POP3 mechanism enables clients to connect to the server, download

messages, and then disconnect, after which the user can work with the

messages offline. Because of this, the client’s message store is said to

be authoritative in a POP3 application. When dial-up connections were

the prevalent form of Internet access, POP3 provided the most

bandwidth-efficient method of accessing incoming email.

POP3 is designed to

keep the server side of the application as simple as possible, leaving

the majority of the messaging tasks to the client. There are, however,

two potential areas of server complexity. One involves the numbering of

the messages in a mailbox when a user downloads and deletes some, but

not all of the waiting messages. Instead of numbering the messages

consecutively, and renumbering the messages when the client deletes some

of them, most POP3 implementations use a technique called Unique Identification Listing (UIDL) to assign a permanent, unique identifier to each message in the mailbox.

The other potential problem is one of authentication security. The POP3

standard contains no provision for the use of encrypted passwords, and

some implementations still require clients to transmit passwords in

plain text. There are, however, a number of POP3 implementations that

use security extensions to protect passwords and prevent unauthorized

access to email accounts.

POP3 servers use the well-known port number 110 for client connections, and many implementations can use Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) or Transport Layer Security (TLS) to encrypt the contents of the email messages during download.

2.3. Internet Message Access Protocol 4 (IMAP4)

IMAP4 is another “pull”

protocol that clients can use to obtain their email messages from a

server. However, unlike POP3, IMAP4 is designed to leave the messages

stored on the server and enable users to work with them there. An IMAP4

client is able to store copies of email messages on the local drive, but

the authoritative message store resides on the server.

Most email clients can

support both IMAP4 and POP3 connections to a server. IMAP4 connections

use well-known port number 143. ISPs tend to provide their customers

with POP3 mailboxes because they require fewer server resources and much

less server storage. Web–based email implementations, on the other

hand, often use IMAP4 to display a user’s message store in a web browser

interface.

IMAP4 places a much greater

burden on the server than POP3, not only because the server must

maintain a message store for each user but also because the IMAP4 server

provides more functions than a POP3 server. IMAP4 clients can create

folders to organize email messages, move messages around between

folders, and run searches for specific messages. Searching, in

particular, can be a highly resource-intensive task, depending on the

size of the mailbox.

IMAP4 also provides

distinct advantages for the user. When a client connects to a server

using IMAP4, access to the user’s message store is almost immediate

because the client is displaying the contents of the mailbox as it

exists on the server. By contrast, a POP3 client must check the server

for new messages, download them, and integrate the messages into the

client’s data store before the user can begin working with them.

Because IMAP4 stores

messages on the server, users can access their mailboxes from different

locations without causing problems. For this reason, IMAP4 is a popular

solution on college campuses, in which students in a computer center

might use a different system each time they access their email. IMAP4

also enables multiple users to access the same mailbox simultaneously,

while a POP3 mailbox can support only one connected user at a time. This

can be highly useful in a business environment, such as a help desk

that has several people servicing a single email help line.

2.4. Exchange Server 2010 Functions

Exchange Server 2010, although

based on industry standards, is a proprietary mail and scheduling

product that is designed to provide clients with access to local and

Internet email, shared

calendars and scheduling, task management, and a unified messaging

interface that can route other types of traffic, such as voice mail and

faxes, to a user’s inbox. Windows SBS 2011 automatically installs

Exchange Server 2010 with the Windows Server 2008 R2 operating system

and configures it to provide these services to your network users.

When you run the Add A New

User Account Wizard in the Windows SBS Console, the wizard creates an

Exchange Server mailbox for each of your new users using the email address you specify. By default, the email

address consists of the user’s account name and the name of the

Internet domain you specified in the Internet Address Management Wizard,

as in the example [email protected].

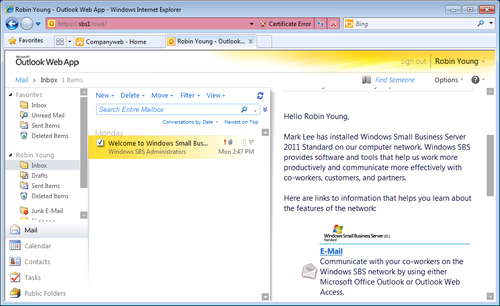

Users can access their mailboxes using the Office Outlook Web Access (OWA) site, shown in Figure 4,

which Windows SBS 2011 creates by default. Users can also access their

Exchange Server mailboxes with Microsoft Outlook, but this client is not

included with Windows SBS 2011. You must purchase an appropriate

edition of Microsoft Office 2010 for your client computers to obtain the

Outlook client.

The Exchange Server 2010

implementation in Windows SBS 2011 includes POP3 and IMAP4 servers among

its capabilities, but by default, the server does not start the

Exchange POP3 and Exchange IMAP4 services, which prevents clients from

using these protocols to access their Exchange Server mailboxes. If

desired, you can start the POP3 or IMAP4 service on your Windows SBS

2011 server, enabling users to access their mailboxes using clients such

as Windows Live Mail, the Windows Mail client included in Windows

Vista, and the Outlook Express client in Windows XP. However, this

solution provides users with email access only. These clients do not support the scheduling and task management features in Exchange Server.